Potential PPP projects must undergo an appraisal process to ensure that developing and implementing them makes sense. For any proposed PPP project, there are five key criteria that governments should consider when deciding whether or not to pursue a project as a PPP:

- Feasibility and economic viability of the project (Assessing Project Feasibility and Economic Viability)—whether the underlying project makes sense, irrespective of the procurement model. First, this means confirming that the project fits in with national development and sector strategies, policy priorities, and sector and infrastructure plans. It then involves feasibility studies to ensure that the project is technically feasible, and the technology is easily available in the market and unlikely to become obsolete in the medium term; and economic appraisal to check that the project is cost-benefit justified, and represents the least-cost approach to delivering the expected benefits. Attention should be paid to environmental and social issues (E&S), addressed in Environmental and Social Studies and Standards.

- Commercial viability (Assessing Commercial Viability)—whether the project is likely to attract good-quality sponsors and lenders by providing robust and reasonable financial returns. This is subsequently confirmed through the tender process.

- Value for money of the PPP (Assessing Value for Money of the PPP)—whether developing the proposed project as a PPP can be expected to best achieve value for money compared to other options. This includes comparing against public procurement (where that would be an option) and other possible PPP structures. Some countries, like Australia and India, mandate the development of a public sector comparator during the appraisal process. This is an estimate of the hypothetical, whole-of-life cost of the project if financed by government under traditional procurement. This ensures that the proposed structure provides the best value for money.

- Fiscal responsibility (Assessing Fiscal Implications)—whether the project’s overall revenue requirements are within the capacity of users and the public authority to pay for the infrastructure service. This involves checking the fiscal cost of the project—both in terms of regular payments and fiscal risk—and establishing whether this can be accommodated within prudent budget and other fiscal constraints.

- Project management (Assessing the Ability to Manage the Project)—whether the contracting agency has the authority, capacity, and fiscal resources to prepare and tender the project, and to manage the contract during its term.

These criteria (with some variations) are described in more detail in Chapter 5: “Public-Sector Investment Decision” in Yescombe’s book on PPPs (Yescombe 2007); Chapter 4: “Selecting PPP Projects” in Farquharson et al's book on PPPs (Farquharson et al. 2011), Module 3 of the Caribbean PPP Toolkit (Caribbean 2017), and Chapter 1: “Project Identification” in the EPEC Guide to Guidance (EPEC 2011b).

The Five Case Model

The United Kingdom has developed a methodology for project assessment called the Five Case Model. The methodology can be applied to every type of project, whether PPP or not. It provides a comprehensive framework for assessing projects. It consists of looking at a project through five different lenses, or cases, as follows:

- The Strategic Case—covers the rationale for the project, outlining its scope and objectives, and places it within an overall strategic and policy context; in short it should make the case for change.

- The Economic Case—this demonstrates that a wide range of options has been considered taking into account relevant political, economic, social, technical, legal and environmental factors. A cost-benefit analysis should be conducted on a short list of options to determine which one offers best value. For a PPP, it should demonstrate that using private finance offers best value for money for the public sector. In the United Kingdom, a qualitative evaluation and a numerical quantitative evaluation are used to test this.

- The Commercial Case—demonstrates that the project is commercially viable and bankable; that the supplier market has been tested; and that the contract is well developed with an appropriate risk allocation.

- The Financial Case—demonstrates that the project is affordable and explains what amount is to be funded by the contracting authority, what amount will be funded by the central government funding, and what user of the facility will pay.

- The Management Case—this should demonstrate that all arrangements are in place to ensure the successful delivery of the project, namely, that the project is properly staffed and resourced, with appropriate governance arrangements, advisers and timetable, so that it can be procured on time and on budget.

Guidance on this can be found in the United Kingdom Green Book (UK 2011a) and Five Case Model methodology (Flanagan and Nicholls 2007).

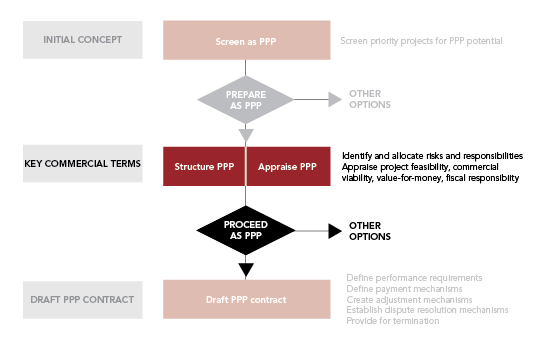

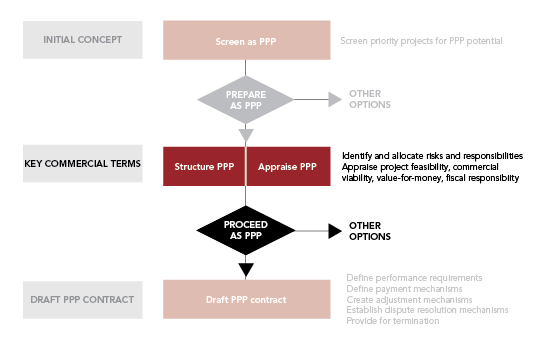

Appraising PPP Projects shows how project appraisal fits in to the overall PPP process. Initial assessment against each criterion is typically done at the project identification and initial screening stage, as described in Identifying PPP Projects. Detailed appraisal is usually first conducted as part of a detailed business case alongside developing the PPP project structure, as described in Structuring PPP Projects. For example, assessing the value for money of the PPP depends on risk allocation, an important part of PPP structuring.

PPP appraisal is typically re-visited at later stages. The final cost, affordability and value for money is not known until after procurement is complete, when the government must make the final decision to sign the contract. Many governments require further appraisal and approval at this stage.

Appraising PPP Projects

Subsections

- Assessing Project Feasibility and Economic Viability

- Environmental and Social Studies and Standards

- Assessing Commercial Viability

- Assessing Value for Money of the PPP

- Assessing Fiscal Implications

- Assessing the Ability to Manage the Project

Key References

PPP Project Appraisal

- Yescombe, E.R. 2007. Public-Private Partnerships: Principles of Policy and Finance. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Chapter 5: The Public-Sector Investment Decisions describes the factors that a public authority should consider when deciding to invest in new public infrastructure via a PPP, and how these can be assessed.

- Farquharson, Edward, Clemencia Torres de Mästle, E. R. Yescombe, and Javier Encinas. 2011. How to Engage with the Private Sector in Public-Private Partnerships in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: World Bank. Chapter 4: Selecting PPP Projects describes how governments can assess whether a project can and should be developed as a PPP, including considering affordability, risk allocation, value for money, and market assessments.

- EPEC. 2011b. The Guide to Guidance: How to Prepare, Procure, and Deliver PPP Projects. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, European PPP Expertise Centre. Chapter 1: “Project Identification, Section 1.2: Assessment of the PPP Option” describes and provides links to further references on how governments assess whether a proposed PPP is affordable, whether risks have been allocated appropriately, whether it is bankable, and will provide value for money.

- ZA. 2004a. Public Private Partnership Manual. Pretoria: South African Government, National Treasury. Module 4: “PPP Feasibility Study” describes in detail the analysis required to support a business case for a PPP project. This includes needs and options analysis, project due diligence, value for money analysis, and economic valuation.

Commercial Viability Analysis

- ADB. 2008. Public-Private Partnership Handbook. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Chapter 3.5 on assessing commercial, financial and economic issues, includes an overview of a typical financial model of a PPP project, and how it is used to assess commercial viability.

- Farquharson, Edward, Clemencia Torres de Mästle, E. R. Yescombe, and Javier Encinas. 2011. How to Engage with the Private Sector in Public-Private Partnerships in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: World Bank. Chapter 8: “Managing the Initial Interface with the Private Sector” describes how to prepare and carry out a market sounding exercise.

- 4ps. Accessed March 16, 2017. "Public Private Partnerships Programme (4Ps) website." Provides tips and guidance on implementing market sounding, and a case study on the experience of market sounding for a hospital in the United Kingdom.

- Grimsey, Darrin, and Mervyn K. Lewis. 2009. "Developing a Framework for Procurement Options Analysis." In Policy, Finance and Management for Public-Private Partnerships, edited by Akintola Akintoye and Matthias Beck. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell. Describes the advantages of market sounding and sets out a market sounding exercise for a hypothetical example hospital PPP project.

- SG. 2012. Public Private Partnership Handbook. Version 2. Singapore: Government of Singapore, Ministry of Finance. Requires implementing agencies to conduct market sounding before pre-qualification, and describes the type of information that should be shared at this stage.

Fiscal Analysis

- Irwin, Timothy C. 2003. "Public Money for Private Infrastructure: Deciding When to Offer Guarantees, Output-Based Subsidies, and Other Fiscal Support." Working Paper No. 10. Washington, DC: World Bank. Section 6: “Comparing the Cost of Different Instruments” describes how governments can assess the cost of various types of fiscal support to PPPs—including output-based grants, in-kind grants, tax breaks, capital contributions, and guarantees.

- OECD. 2008a. Public-Private Partnerships: In Pursuit of Risk Sharing and Value for Money. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Chapter 3: “The Economics of Public-Private Partnership: is PPP the Best Alternative” describes how the affordability of a PPP can be assessed.

- EPEC. 2011a. State Guarantees in PPPs: A guide to better evaluation, design, implementation, and management. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, European PPP Expertise Centre. Sets out the range of state guarantees used in PPPs—encompassing finance guarantees, and contract provisions such as revenue guarantees, or termination payments. Describes why and how they are used, how their value can be assessed, and how they can be best managed.

- AU. 2016a. National Public Private Partnership Guidelines - Volume 4: Public Sector Comparator Guidance. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Section 16: “Identifying, allocating, and evaluating risk” describes in detail different methodologies for valuing risk (and contingent liabilities) in PPPs.

- Irwin, Timothy C. 2007. Government Guarantees: Allocating and Valuing Risk in Privately Financed Infrastructure Projects. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. Comprehensively describes why and how governments accept contingent liabilities under PPP projects by providing guarantees. Describes in detail how the value of these guarantees can be calculated, with examples.

- CO. 2012b. Obligaciones Contingentes: Metodologías del caso colombiano. Bogotá: Gobierno de Colombia, Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público. Presentation by the Ministry of Finance of Colombia on the conceptual and legal frameworks, and methodologies used in Colombia for managing contingent liabilities.

- CL. 2016. Informe de Pasivos Contingentes 2016. Santiago: Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio de Hacienda, Dirección de Presupuestos. Describes the conceptual framework for assessing contingent liabilities and the government’s contingent liability exposure. This includes quantitative information (maximum value and expected cost) on government guarantees to PPP projects (concessions).

- Irwin, Timothy C., and Tanya Mokdad. 2010. Managing Contingent Liabilities in Public-Private Partnerships: Practice in Australia, Chile, and South Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank. Describes the approach in the State of Victoria, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, to approvals analysis, and reporting of contingent liabilities under PPPs. Appendix 1 describes in detail the methodology used in Chile to value revenue and exchange rate guarantees.

- PE Pasivos. Accessed March 8, 2017. "Pasivos Contingentes." Peru, Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas. URL. Presents a methodology, results, and background reports on the value of contingent liabilities under PPP projects in Peru.

Value for Money Analysis

- UK. 2011b. Quantitative assessment: User Guide. London: UK Government, HM Treasury. Provides detailed guidance and a worked example on the quantitative approach to value for money assessment—calculating the Public Sector Comparator, and comparing it to the PPP reference model, as well as an excel spreadsheet tool for carrying out the analysis.

- Grimsey, Darrin, and Mervyn K. Lewis. 2005. "Are Public Private Partnerships value for money?: Evaluating alternative approaches and comparing academic and practitioner views." Accounting Forum 29(4) 345-378. Describes approaches to assessing value for money in PPPs, and sets out in detail the PSC approach and its pros and cons.

- OECD. 2008a. Public-Private Partnerships: In Pursuit of Risk Sharing and Value for Money. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Chapter 3: “The Economics of Public-Private Partnership: is PPP the Best Alternative” describes the determinants of value for money in a PPP, and how it is typically assessed.

- WB. 2009a. "Toolkit for Public-Private Partnerships in Roads and Highways." World Bank. URL. Section on value for money and the PSC describes the logic behind value for money analysis, how the PSC is used, and some of its shortcomings.

- Leigland, James, and Chris Shugart. 2006. "Is the public sector comparator right for developing countries? Appraising public-private projects in infrastructure." Gridlines Note No. 4. Washington, DC: Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility. Summarizes common criticisms of PSC analysis, and describes whether and how using PSC analysis may make sense in developing country contexts.

- AU. 2016a. National Public Private Partnership Guidelines - Volume 4: Public Sector Comparator Guidance. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Provides detailed guidance on calculating the public sector comparator, and a worked example, including extracts from the excel model used.

- CO. 2010. Nota Técnica: Comparador público-privado para la selección de proyectos APP (Borrador para Discusion). Bogotá: Gobierno de Colombia, Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público. Introduces the PSC methodology, explains all the analytic steps, and provides a worked example.

- Shugart, Chris. 2006. Quantitative Methods for the Preparation, Appraisal, and Management of PPI projects in Sub-Saharan Africa. Midrand, South Africa: NEPAD. Describes some methodological inconsistencies and challenges with the PSC—focusing on two related issues: which is the appropriate discount rate to use when calculating present values, and how the cost of risk should be considered.

- Grimsey, Darrin, and Mervyn K. Lewis. 2004. "Discount debates: Rates, risk, uncertainty and value for money in PPPs." Public Infrastructure Bulletin 1(3). Describes the implications of the choice of discount rate in comparing PPP and public procurement, and the relationship between discount rates and risk allocation.

- Gray, Stephen, Jason Hall, and Grant Pollard. 2010. The public private partnership paradox. Brisbane, Australia: University of Queensland. Provides a more theoretically-driven discussion of the choice of discount rate for evaluating PPPs, compared with public procurement projects—emphasizing the difference between discounting future cash outflows and inflows.

- EPEC. 2011c. The Non-Financial Benefits of PPPs: A Review of Concepts and Methodology. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, European PPP Expertise Centre. Describes the shortcomings of standard PSC analysis, which assesses fiscal costs but does not consider non-financial costs and benefits. Suggests an alternative approach incorporating non-financial benefits in the PSC.

- NZ. 2016. "Public Private Partnership (PPP) Guidance." The Treasury. URL. Chapter 5: “Procurement Options” sets out the logic and analysis for assessing whether procuring a project as a PPP is likely to provide value for money. This includes a simple, quantitative cost-benefit comparison of PPP and public procurement.

Visit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.