Designing PPP Contracts

Photo Credit: Image by Pixabay

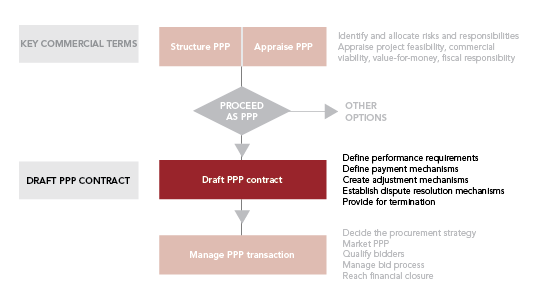

The PPP contract is at the center of the partnership, defining the relationship between the parties, their respective rights and responsibilities, allocating risk, and providing mechanisms for dealing with change. In practice, the PPP contract can encompass several documents and agreements, as described in What is the PPP Contract? Most PPP projects present a contractual term between 20 and 30 years; others have shorter terms; and a few last longer than 30 years. The term should always be long enough for the private party to adopt a whole-life costing approach to project design and service management, guaranteeing service performance at the lowest cost. The term depends on the type of project and on policy considerations—the project should be needed over the term of the contract, the private party should be able to accept responsibility for service delivery over its term, and the procuring authority should be able to commit to the project for its term. The availability of finance, and its conditions, may also influence the term of the PPP contract. This section uses the term PPP contract to mean the contractual documents that govern the relationship between the public and private parties to a PPP. In practice, the PPP contract may comprise more than one document. For example, a PPP to design, build, finance, operate, and maintain a new power plant, with power supplied in bulk to a government-owned transmission company may be governed by a power purchase agreement (PPA) between the transmission company and the PPP company, as well as an implementation agreement between the responsible government ministry and the PPP company. Each agreement may, in turn, refer to schedules or annexes to set out particular details—for example, detailed performance requirements and measures. In addition to the PPP contract, there will also be numerous contracts between the SPV and its suppliers and financiers. Chief among them would be financing agreements between the SPV and its lenders, and shareholder agreements between equity investors (see How PPPs Are Financed for more on the PPP contractual structure). The PPP contract may not be effective until these other contractual agreements are in place. The EPEC Guide to Guidance (EPEC 2011b, 23) lists topics that should be covered in a typical PPP contract—the Examples of Standardized PPP Contracts and Contract Clauses provide further examples. The PPIAF Toolkit for PPP in Highways (WB 2009a) section on contracts describes the range of contractual agreements typically involved for different types of PPP. As shown in PPP Contract Design Stage, the draft PPP contract is generally needed before a Request for Proposal (RFP) is issued. Detailed contract design takes significant time and resources—including from expert advisors. Approval is often required before embarking on detailed design and investing these resources. The draft PPP contract is typically included with the RFP sent to prospective bidders. In some cases, the PPP contract issued with the RFP cannot be changed. In others, it may be changed because of interaction with bidders during the transaction process. Australia National PPP Guidelines Roadmap (AU 2015) and the South Africa PPP Manual (ZA 2004a) provide an overview of PPP contract development and how it progresses at each stage of implementing the PPP. PPP Contract Design Stage A well-designed contract is clear, comprehensive, and creates certainty for the contracting parties. Because PPPs are long-term, risky, and complex, PPP contracts are necessarily incomplete—that is, they cannot fully predict future conditions. This means the PPP contract needs to have flexibility built in to enable changing circumstances to be dealt with as far as possible within the contract, rather than resulting in renegotiation or termination. The aim of PPP contract design is therefore to create certainty where possible, and bounded flexibility where needed—thereby retaining clarity and limiting uncertainty for both parties. This is achieved by creating a clear process and boundaries for change. To implement this style of contract in practice requires strong contract management institutions, as described in Managing PPP Contracts. Where possible, involving the future contract manager in designing or reviewing the PPP contract can help ensure that change management processes are implementable in practice. PPP contract design is a complex task. This section briefly sets out some key considerations—and provides links to tools, examples, and further resources—in five areas of PPP contract design: Together, these sets of provisions define the risk allocation under the contract. Obviously, the aim must be to draft these provisions so that the risk allocation chosen (as set out in Structuring PPP Projects) is achieved. The provisions dealing with adjustment mechanisms and dispute resolution are intended to avoid the need for renegotiation, by allowing changes to be made, and problems resolved, within the framework provided by the contract. Some countries have made efforts to standardize elements of PPP contract design to reduce the considerable time and cost frequently involved in preparing and finalizing a given PPP contract. They have developed standardized contractual provisions or even complete standardized PPP contracts—Examples of Standardized PPP Contracts and Contract Clauses provides some examples. Other countries have chosen to incorporate certain elements of PPP contract design in legislation that governs all PPP contracts, as described in PPP Legal Framework. For example, in Chile the dispute resolution mechanism is established in the Concessions Law. The World Bank Group’s Report on Recommended PPP Contractual Provisions (WB 2017e) sets out and analyzes certain contractual provisions dealing with particular legal issues encountered in virtually every PPP contract, such as force majeure, termination rights and dispute resolution. Another useful resource is the World Bank's online PPP in Infrastructure Resource Center (PPPLRC-Types)—this website hosts a collection of actual PPP contracts and sample agreements for a range of contract types and sectors. To review the impact of contractual clauses on statistical classification, the 2016 Eurostat Guide to the Statistical Treatment of PPPs (EPEC 2016) reviews a large set of PPP contractual provisions typical in European government-pays PPP contracts. Examples of Standardized PPP Contracts and Contract Clauses Designing PPP Contracts Visit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

Aim of PPP contract design

JURISDICTION

STANDARD

LINKS

Australia

Guidelines issued by Infrastructure Australia on standard commercial principles for social and economic infrastructure PPPs

Infrastructure Australia's PPP Guidelines (AU 2017): Volume 3 on social infrastructure and Volume 7 on economic infrastructure.

India

Descriptions of model agreements for PPP in a range of transport sectors

Former Planning Commission (IN 2014d), (IN 2009)

Netherlands

Standard PPP contract for DBFM in buildings and DBFMO in infrastructure

Ministry of Finance Publications (NL 2017)

New Zealand

Draft standard PPP contract

National Infrastructure Unit (NZ 2013)

Philippines

Sample contracts for PPP in bulk water supply, ICT, solid waste management, and urban mass transit. The PPP Center is currently developing standardized terms for broader application

Public-Private Partnership Center: PEGR Sample Contracts (PEGR 2009)

South Africa

Standardized PPP provisions published alongside the South Africa PPP Manual

National Treasury Standardized PPP Provisions (ZA 2004c)

United Kingdom

Standardized contracts for PFI projects; includes extensive guidance on each element of the contract

Her Majesty’s Treasury: Standardized contracts (UK 2012c)

Subsection

Key References

Find in pdf at PPP Reference Guide - PPP Cycle or visit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

Related Content

INTRODUCTION

Page Specific DisclaimerVisit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

PPP BASICS: WHAT AND WHY

Page Specific DisclaimerVisit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

Featured Section LinksESTABLISHING THE PPP FRAMEWORK

Page Specific DisclaimerVisit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

PPP CYCLE

Page Specific DisclaimerVisit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.

Identifying PPP Projects

Type of ResourceAppraising Potential PPP Projects

Type of ResourceStructuring PPP Projects

Type of ResourceDesigning PPP Contracts

Type of ResourceManaging PPP Transactions

Type of ResourceManaging PPP Contracts

Type of ResourceDealing with Unsolicited Proposals

Type of ResourceKey References - PPP Cycle

Type of Resource