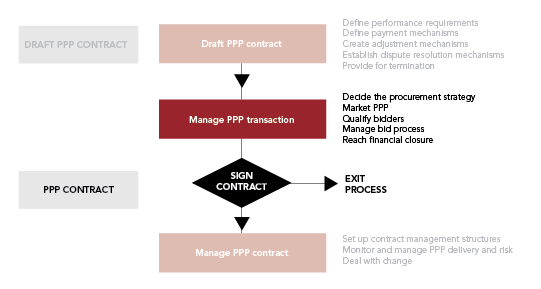

In the transaction stage, the government selects the private party that will implement the PPP. This process will also determine the effective terms of the contract. This stage follows the structuring, appraisal, and detailed preparation of the PPP described in the previous sections of this module. It concludes when the PPP reaches financial close—that is, when the government has selected and signed a contract with a private party, and the private party has secured the necessary financing and can start deploying it in the project.

Transaction Stage of PPP Process

The aim of the PPP transaction stage is twofold:

- To select a competent firm or consortium

- To identify the most effective and efficient solution to the proposed project’s objectives—both from a technical, and value for money perspective

To the latter end, the process typically establishes some of the key quantitative parameters of the contract, such as the amounts the government will pay or the fees users will pay for the assets and services provided. Achieving these objectives generally requires a competitive, efficient, and transparent procurement process, as outlined in the PPIAF toolkit for PPPs in roads and highways procurement section (WB 2009a) under competitive bidding; in the Caribbean PPP Toolkit (Caribbean 2017, Module 5); and by Farquharson et al (Farquharson et al. 2011, 112) in describing the outcome of the procurement phase.

Since most governments use a competitive selection process to procure PPP contracts as the best way to achieve transparency and value for money, this section assumes a competitive process is followed. In practice, there may be a few circumstances where direct negotiation could be a good option. However, many reasons put forward to negotiate directly are spurious, as described in Competitive Procurement or Direct Negotiation.

Competitive Procurement or Direct Negotiation

A competitive selection process is the recommended route to procure PPP contracts. Key advantages are transparency and use of competition to choose the best proposal—the mechanism most likely to result in value for money. The alternative to a competitive process is to negotiate directly with a private firm.

There can be good reasons to negotiate directly, but these are relatively few—see for example Kerf et al’s guide to concessions (Kerf et al. 1998, 109–110) and the World Bank report on the Framework for Unsolicited Proposals' (WB 2017d) sections on direct negotiation. These reasons include:

- Small projects with known costs, where the costs of a competitive process would be prohibitively high given the level of expected returns;

- Cases where there is good reason to believe there would be no competitive interest—for example, small extensions of an asset for which a contract is already in place; and

- The need for rapid procurement in the case of emergencies and natural disasters, where speed may outweigh value for money considerations, although this is often not the case when dealing with PPPs, better able to deal with long-term needs than with urgencies.

Whenever a government allows for direct negotiations under specific circumstances, these circumstances and their associated criteria should be clearly specified in the procurement legal framework. Direct negotiations should only be pursued once suitable safeguards for value for money, transparency, accountability, and public interest have been established and operationalized.

On the other hand, several reasons commonly put forward to negotiate directly with a private proponent of a PPP can be misleading—see the section in PPIAF’s toolkit for PPPs in roads and highways (WB 2009a), Module 5: Procurement on overall principles for procurement. For example, some argue direct negotiation is faster—though in practice, challenges often make the process longer. Often, direct negotiation is also considered when a PPP idea originated from an unsolicited proposal from a private company. However, there are ways to introduce competition in this case that help ensure value for money from the resulting project, as described in Dealing with Unsolicited Proposals. Based on these considerations, some countries do not allow non-competitive procurement processes at all,such as Brazil, under the Federal PPP Law of 2004 (BR 2004a). Elsewhere, direct negotiation may be allowed in particular circumstances. For example, Puerto Rico’s PPP Act allows for direct negotiations if the investment value is under $5 million, there is lack of interest after issuing an RFP, the normal procurement process is burdensome, unreasonable, or impractical, or the technology required is only available from a single company (PR 2009, Article 9.(b).ii).

Direct Negotiation of Unsolicited Proposals outlines several preparation requirements for those procuring authorities that need to directly negotiate an unsolicited proposal.

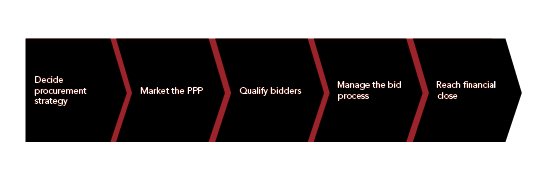

Transaction Steps

The transaction stage typically includes the following five steps, as shown in Transaction Steps:

- Deciding on a procurement strategy, including the process and criteria for selecting the PPP contractor

- Marketing the upcoming PPP project to interest prospective bidders (as well as potential lenders and sub-contractors)

- Identifying qualified bidders through a qualification process, either as a separate step before requesting proposals or as part of the bidding process

- Managing the bid process, including preparing and issuing a Request for Proposal, interacting with bidders as they prepare proposals, and evaluating bids received to select a preferred bidder

- Executing the PPP contract and ensuring all conditions are met to reach contract effectiveness and financial close—this may require final approval from government oversight agencies

Managing PPP Transactions describes each of these steps, and provide further resources and tools for practitioners interested in managing PPP transactions.

Subsections

- Deciding the Procurement Strategy

- Marketing the PPP

- Qualifying Bidders

- Managing the Bid Process

- Achieving Contract Effectiveness and Financial Close

Key References

Managing PPP Transactions

- WB. 2009a. "Toolkit for Public-Private Partnerships in Roads and Highways." World Bank. URL. Module 5: “Implementation and Monitoring, Stages 3: Procurement,” and 4: “Contract Award.”

- Farquharson, Edward, Clemencia Torres de Mästle, E. R. Yescombe, and Javier Encinas. 2011. How to Engage with the Private Sector in Public-Private Partnerships in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: World Bank. Chapter 9: “Managing Procurement” talks through each stage of the procurement process. Includes a case study of the Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, South Africa describes the procurement process for the hospital, which included a multi-variable bid evaluation approach.

- Kerf, Michael, R. David Gray, Timothy Irwin, Celine Levesque, Robert R. Taylor, and Michael Klein. 1998. "Concessions for Infrastructure: A guide to their design and award." World Bank Technical Paper No. 399. Washington, DC: World Bank. Section 4: “Concession Award” provides detailed guidance and examples on choosing the procurement process, pre-qualification and shortlisting, bid structure and evaluation, and bidding rules and procedures.

- GIH. 2016b. "GI Hub Launches Project Pipeline." Press release. Global Infrastructure Hub. December 6. URL. The GI Hub Pipeline is a freely-available platform on which governments can market their PPP projects to prospective bidders, lenders and other key private sector stakeholders.

- PPIAF. 2006. Approaches to Private Sector Participation in Water Services: A Toolkit. Washington, DC: Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility. Section 9: “Selecting an Operator” provides guidance on choosing a procurement method, setting evaluation criteria, managing the bidding process, and dealing with other issues.

- EPEC. 2011b. The Guide to Guidance: How to Prepare, Procure, and Deliver PPP Projects. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, European PPP Expertise Centre. Section 2: “Detailed Preparation” includes information on selecting the procurement method and bid evaluation criteria. Section 3: “Procurement” describes the bidding process, through to finalizing the PPP contract, with detailed information on reaching financial close.

- UK. 2008. Competitive Dialogue in 2008: OGC/HMT joint guidance on using the procedure. London: UK Government, HM Treasury. Describes and provides guidance on carrying out the competitive dialogue procurement procedure. Describes some challenges—such as receiving only one bid. Also describes the post-bid stages, with guidance on issues that may be resolved post-bid.

- Yescombe, E.R. 2007. Public-Private Partnerships: Principles of Policy and Finance. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Section 6.5 “Due Diligence” describes some of the issues the implementing agency should check before contracting is completed—including describing the requirements to reach financial close.

- KPMG. 2010. PPP Procurement: Review of Barriers to Competition and Efficiency in the Procurement of PPP Projects. Sydney: KPMG Australia. Draws on a survey of PPP practitioners, to provide recommendations for how the efficiency of PPP procurement processes can be improved, and barriers to entry reduced. The recommendations focus on improving the efficiency of the PPP procurement process, as well as touching on the pros and cons of governments contributing...

- ADB. 2008. Public-Private Partnership Handbook. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Section 7: “Implementing a PPP” describes several aspects of PPP procurement, including selecting the process, pre-qualification, bid evaluation, and preparing the tender documentation.

- WB. 2011c. Guidelines Procurement of Goods, Works, and Non-Consulting Services under IBRD Loans and IDA Credits and Grants by World Bank Borrowers. Washington, DC: World Bank. Sets out the procurement procedures that any project receiving World Bank funding must use.

- Dumol, Mark. 2000. The Manila Water Concession: A key government official's diary of the world's largest water privatization. Washington, DC: World Bank. Describes in detail the entire process of the Manila water concession, from deciding on the best option for privatization, to running the tender process, to dealing with the many issues that emerged.

- Engel, Eduardo, Ronald Fischer, and Alexander Galetovic. 2002. "A New Approach to Private Roads." Regulation 25 (3). Describes and explains the advantages of the Least Present Value of Revenue criterion introduced in Chile’s toll road program.

- Guasch, José Luis. 2004. Granting and Renegotiating Infrastructure Concessions: Doing it right. Washington, DC: World Bank. Chapter 7 provides guidance on optimal concession design, drawing from the preceding analysis of the prevalence of renegotiation of concession contracts in Latin America. Includes guidance on selecting appropriate evaluation criteria.

- BR. 2004. Lei No. 11.079 de 30 de dezembro de 2004. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil. Clarifies process for PPPs, including describing the contents of the RFP documents, and the possible evaluation criteria.

- BR. 1995. Lei No. 8.987 de 13 de fevereiro de 1995. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil. Sets out the tendering procedures for (user-pays) concessions in Brazil (which also apply to government-pays PPPs).

- CL. 2010b. Ley y Reglamento de Concesiones de Obras Públicas: Decreto Supremo MOP Nº 900. Santiago: Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio de Obras Públicas. Chapter III sets out in some detail the procurement process for PPPs, including pre-qualification, the bid process, possible evaluation criteria, and processes for contract award.

- EG. 2011. Executive Regulation of Law No. 67 of 2010, Issued through Prime Minister Decree No. 238 of 2011. Cairo: Government of Egypt. Part Three sets out in detail the tendering, awarding, and contracting procedures for PPPs, including pre-qualifications, tender stage, competitive dialogue, and awarding and contracting procedures. Also specifies an approach for appeals.

- IN. 2007. Panel of Transaction Advisors for PPP Projects: A Guide for Use of the Panel. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Finance. This users’ guide describes the processes and the tasks involved in appointing a transaction advisor for a PPP transaction using the panel

- MX. 2014. Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público. Mexico City: Gobierno de México, Cámara de Diputados. Sets out the rules for carrying out tender processes in Mexico. It includes the possible contracting options—public tenders, sole sourcing, and direct invitations to bid to at least three potential bidders.

- PH. 2006. The Philippine BOT Law R.A. 7718 and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. Revised 2006. Manila: Public-Private Partnership Center. Implementing Rules 3-11 set out in detail the procurement process and requirements at each stage: pre-qualification, bid process and evaluation, when and how a negotiated procedure may be used, dealing with unsolicited proposals, and contract award and signing.

- ZA. 2004a. Public Private Partnership Manual. Pretoria: South African Government, National Treasury. Module 5: Procurement sets out the procurement process and guidance: including pre-qualification, issuing the RFP, receiving and evaluating bids, negotiating with the preferred bidder, and finalizing the PPP agreement management plan.

- AU. 2015. National Public Private Partnership Guidelines - Volume 2: Practitioners' Guide. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Sets out key project phases, including three procurement phases: Expressions of Interest, Request for Proposal, and Negotiation and Completion. Also provides guidance and protocols for the interactive tender process.

- SG. 2012. Public Private Partnership Handbook. Version 2. Singapore: Government of Singapore, Ministry of Finance. Section 3 sets out PPP procurement process options and principles.

- IN. 2014b. Public-Private Partnership Request for Qualification: Model RFQ Document. New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission. Sets out a model RFQ, with an explanatory introduction.

- PPPLRC. Accessed March 9, 2017. "Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Resource Center website." URL. Provides a library of PPP documents, including a selection of model and example procurement documents.

- WB. 2006c. Procurement of works and services under output-and performance-based road contracts and sample specifications. Sample bidding documents. Washington, DC: World Bank. Includes a comprehensive, sample bidding document, as well as sample specifications in an annex. A foreword also provides some overview guidance.

- CO. 1993. Ley 80 de 1993. Bogotá: Congreso de Colombia. General procurement law, which also applies to PPPs, defines who is authorized to carry out tender processes transparency requirements, and the contents of the tender documents, and sets out the structure of the awarding procedures.

- CO. 2007. Ley 1150 de 2007. Bogotá: Congreso de Colombia. Sets out rules to ensure the objective selection of the winning bid, procedures to verify the veracity of the information presented by bidders.

- IN. 2014a. Public-Private Partnership Model RFP Document. New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission. This report provides a Request for Proposal for PPP Projects template as well as a short memorandum on the guidelines for invitation of financial bids for PPP projects.

- IN. 2014c. Model Request for Proposals (RFP): Selection of Technical Consultant. New Delhi: Government of India. Sets out a model RFP with an explanatory introduction.

- VIC. 2001. Practitioners' Guide. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance, Partnerships Victoria. Sets out project phases, as described above, as they apply in the State of Victoria, Australia’s PPP program. Similar to the national approach; includes more detail on the bid evaluation phase.

Visit the PPP Online Reference Guide section to find out more.