Changing Technological Environment

Photo Credit: Image by Pixabay

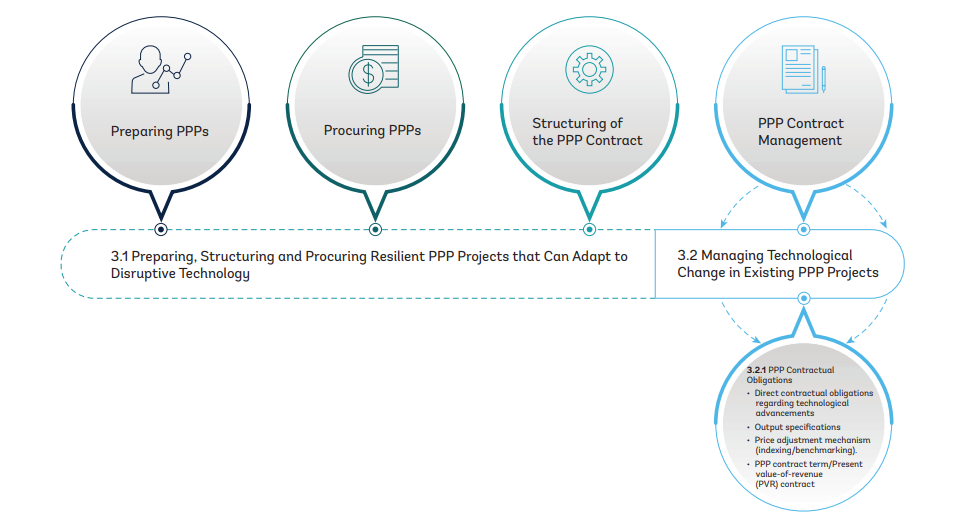

On this page: Defining PPP output specifications that account for technological changes is difficult due to the rapid changes in technology and society.

One of the key benefits of a PPP is that it gives contracting authorities the increased opportunity to take advantage of private sector expertise. That is why the best practice in regard to a PPP transaction is for the government to use output specifications that leave it to the private sector party to be innovative in responding to these requirements and to adopt, for example, innovative technologies. Although most types of technological innovation that either the private partner or the contracting authority wishes to introduce have to be agreed upon by the parties, others may be specified as desired output specifications. The private partner’s obligation is to meet these output specifications. If the private partner is required to integrate specific advancements in technology and fails to do so, it is likely to suffer payment deductions and, above a particular threshold, may be at risk of termination. However, if it complies with the output specifications, the contracting authority cannot simply require it to replace technology because more efficient technological solutions are available unless there is an agreed contractual mechanism fordoing so.1 Box 6: Pan Am Games Athletes’ Village in Canada The project was developed to provide accommodations for the athletes and officials during the Toronto 2015 Pan American and ParaPan American Games. After the games the village became a mixed-use, inclusive and pedestrian-friendly riverside community that includes affordable housing. The Athletes' Village project significantly increased the pace of the West Don Lands revitalization and left Toronto with a beautifully designed lasting legacy of the 2015 Pan/Parapan American Games. The project scope included: The design and construction of the Athletes' Village to provide accommodation for athletes and officials during the Toronto 2015 Games. Construction of new roads and services, such as hydro, sewer and water infrastructure. Conversion of the Athletes' Village into its post-games legacy state: a modern and sustainable neighborhood that includes market and affordable housing on Toronto's waterfront. The project includes several design requirements that relate to disruptive technology, in particular an “intelligent community” element. According to RenewCanada, the “intelligent community” concept builds on the “smart city” idea but encompasses cities, metropolitan areas, and rural regions. The smart community concept is new and evolving because the number of communities using smart technologies to create economic opportunity and improve the quality of life for citizens continues to grow. Accordingly, in the PPP contract the private partner is, for example, required to make ultra-broadband internet access available to all residential units. The private partner manages Beanfield Technology, the exclusive designated service provider to perform various services pertaining to the Intelligent Community system. In addition, the output specifications refer to best industry standards and require the project to perform the work so as to achieve LEED Gold Certification. Source: GIH (Global Infrastructure Hub). 2019. Reference Guide on Output Specifications for Quality Infrastructure. An obligation to operate in accordance with best industry practice as part of the performance requirements may impose some obligations on the private partner—to take on improvements in technology and to ensure that the infrastructure asset is interoperable with other infrastructure or equipment meeting prevailing industry standards (e.g., new technologies used as a standard for high speed trains may require upgrading of the infrastructure network). Defining PPP output specifications that account for technological changes is difficult due to the rapid changes in technology and society. When it is unclear whether or not the technological advancement is or is not a new technical industry standard, if there are doubts about the value added, or if there is the perception that the requested change will lead to considerably higher costs for the private partner or its subcontractors, the most appropriate approach for PPP contract managers may be to treat these situations as contract variations. Also, a proper allocation of the risks associated with technological change suggests that more fundamental and unforeseeable advances in technology are regularly not addressed through output specifications (see also Structuring the PPP contract: addressing risks and opportunities related to technological innovation “Risk allocation”). "If disruptive technology upsets the economic balance of a PPP contract, contract managers need to check carefully whether the PPP contract establishes rules and processes for adjusting the tariff and whether these apply. Otherwise, sector regulators may be able to periodically revise tariffs or to introduce new pricing schemes to capture, for example, cost savings resulting from disruptive technology." Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: The private partner may in general be better placed than the contracting authority to absorb technological obsolescence risk. However, in light of a rapidly changing technological landscape, future PPP contracts may need to take a more nuanced approach. When defining the desired output, contracting authorities need to ensure that the output specifications (including technical requirements, and applicable codes and standards) set out in the PPP contract consider its long-term needs and anticipate changes that are reasonably predictable, such as advancements in battery storage technology or sensor technology for autonomous vehicles with regard to PPP road projects. The easiest way to ensure that the private partner can quantify its risk exposure while adding more flexibility to a PPP contract is to combine a precise description of the demanded output with a cap related to the costs for the technological upgrades or exceptions. If the PPP contract includes a broad variation mechanism, technical improvements that have major cost implications are thus treated as contract variations that are compensated. To incentivize the private partner to identify and implement the latest technology, PPP contracts can ensure that the private partner and the contracting authority share the benefits of any cost savings that are achieved through such innovations. This would also allow contracting authorities and the society at large to benefit from efficiency gains that result from technological progress (see also Section 3.2.2 (i) “Variations management”). In light of rapid technological advancement, some PPP contracts may already impose a specific obligation on the private partner to adopt new technologies for foreseeable developments, such as sensors for autonomous cars, charging stations for electric cars, or off-grid energy production. Supply contracts that are based on global market-based commodity prices are often indexed in the contract to allow for predictability during market fluctuations. The oil and gas industry, for example, relies on long-term contracts with oil or gas price indexes to stabilize the prices during periods of volatility. Exploring ways to index for disruptive technologies is one way to smooth out unpredictable price changes. In liberalized energy markets with corporate PPAs, for example, the COVID-19 crisis has pushed electricity buyers to consider various pricing structures beyond fixed-price. It is already common to incorporate escalation clauses for inflation or to account for foreign exchange fluctuations. Where there is a wholesale market price for renewable energy, other structures are being considered, such as discounts to market structure, wherein the buyer secures a discount to the market (fixed percentage or amount) over the duration of the PPA; in exchange, the buyer provides the power producer with a floor price, sometimes with a clawback to compensate the power producer if prices increase. PPP contracts are long-term agreements between the contracting authority and the private partner, often 20 to 30 years. During the term, the private partner finances and manages construction, maintains and operates the asset, and, at the end of the contract, transfers it back to the contracting authority. The idea of the long-term commitment is to maximize the efficiency of service delivery by incentivizing the private partner to integrate considerations related to future operation and maintenance into the design and construction phase. Most PPP contracts have a fixed term, i.e., unilateral adjustment is not possible unless the PPP contract includes specific provisions that state how the PPP contract can be terminated before the term ends. Some contracts allow for more flexibility. One way to mitigate exogenous demand risk that is discussed with regard to PPP transport projects is to structure them as present value-of-revenue (PVR) contracts. Under a PVR contract, the regulator sets the discount rate and tariff schedule, and firms bid the present value of tariff revenue for which they desire to finance, build, operate, and maintain the infrastructure. The firm that makes the lowest bid gets the concession, which lasts until the present value of tariffs collected equals the winning bid. Consequently, the term of the concession automatically adjusts to demand shocks, resulting in a substantial reduction of demand risk borne by the concessionaire. PVR contracts are often used in Chile for PPP transport projects.2 Conversely, an extension of the contractual term can be helpful when a drop in demand leads to decreased revenue. When mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 crisis reduced the revenue of many transport PPPs under the “user-pays” PPP model, many private partners asked for an extension of the contractual term. In the report Support Mongolia with Solar Energy Price Setting,3 the World Bank and the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) recommended lowering feed- in tariffs that had become unattractive due to the global solar price drop, and offering the private sector investors an extension of the PPAs as an incentive to agree to these changes, so that they would still be able to recover the initial investment costs and achieve the targeted rate of return with a lower tariff (see “Case Study 1: Mongolia – Addressing Disruptive Technology Through Renegotiation and Energy Regulation”). A contract extension can also help the private partner to absorb costs of expensive technological investments (see “Case Study 6: Puerto Rico – Technological Upgrades and Contract Extension for P-22 and P-5 Toll Roads”). If the PPP contract does not provide for a contract extension under exceptional circumstances described in the contract, the extension needs to be renegotiated (see Renegotiation, government step-in rights, termination, and dispute resolution, “Renegotiation”). Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: One way to mitigate exogenous demand risk that is discussed with regard to PPP transport projects is to structure them as present value-of-revenue (PVR) contracts. It could also be advisable to switch to shorter terms or make contractual terms more flexible in sectors that are susceptible to technological change, should the financial model allow.

Footnote 1: GIH (Global Infrastructure Hub). 2020. PPP Risk Allocation Tool 2019 Edition. Footnote 2: Engel, Eduardo, Ronald D. Fischer, Alexander Galetovic, and Jennifer Soto. 2019. Financing PPP Projects with PVR Contracts: Theory and Evidence from the UK and Chile. Footnote 3: World Bank and ESMAP (Energy Sector Management Assistance Program). 2018. Support Mongolia with Solar Energy Price Setting: Final Report.Contractual Obligations to Adjust the Project to a Changing Technological Environment

Output specifications

Direct contractual obligation to adopt and/or integrate new technologies

Indexing and benchmarking

Term of the contract

The Disruption and PPPs section is based on the Report "PPP Contracts in An Age of Disruption" and will be reviewed at regular intervals.

For feedback on the content of this section of the website or suggestions for links or materials that could be included, please contact the PPPLRC at ppp@worldbank.org.

Updated: July 16, 2024

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary for Disruption and PPPs

Disruptive Technology, Infrastructure and PPPs