Adjustments in Exceptional Situations

Photo Credit: Image by Pixabay

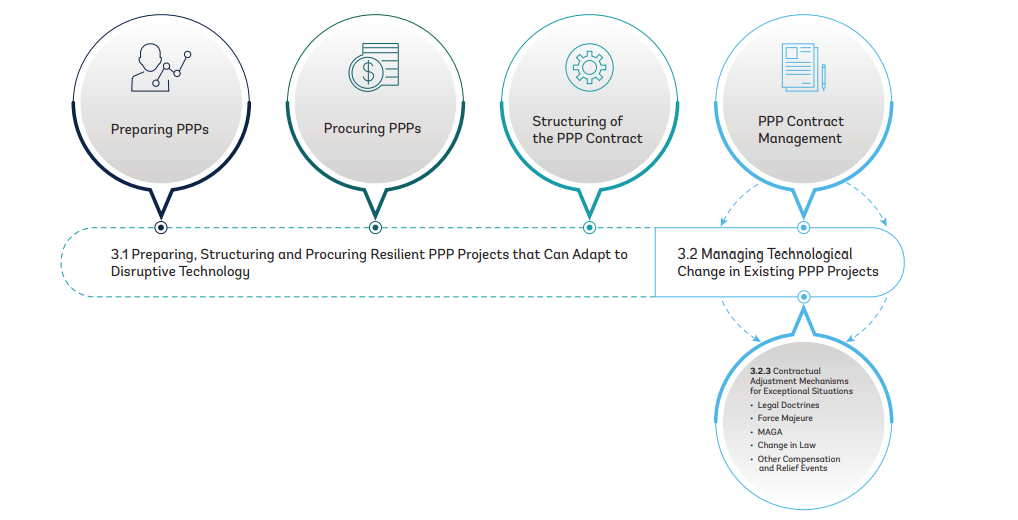

On this page: Where changed circumstances upset the balance of contractual obligations, legal doctrines that are applicable in a number of jurisdictions may give the parties the right to adjust the PPP contract to the new and unexpected conditions.

A long-term unexpected change of circumstances brought on by new technologies might also disrupt the economic underpinnings of a PPP contract fundamentally. This can make it difficult for one party to perform according to the contract or even result in the parties being unable to fulfill their contractual obligations. Generally, a failure by one party to perform contractual obligations gives the other party remedies, including the right to claim compensation or to terminate the contract. However, where the changed circumstances upset the balance of contractual obligations, legal doctrines that are applicable in a number of jurisdictions may give the parties the right to adjust the PPP contract to the new and unexpected conditions. Parties to a PPP contract often agree upfront on a risk allocation that mirrors these legal doctrines to some extent. PPP contractual provisions that can be found in almost all PPP contracts deal with the consequences of a number of specified events that are outside the control of one or both parties, in particular force majeure or MAGA events or change in law. Under these contractual provisions, one or both of the parties may be excused from the performance of certain contractual obligations in whole or in part, or entitled to suspend performance, to claim an extension of time for performance, to claim compensation, or to terminate the contract. Changed circumstances prompted by disruptive technology may give the parties the right to adjust the contract under certain legal doctrines. In some civil law countries, these legal concepts are part of the national law that is applicable to a PPP contract. In other cases, the concepts have become part of the PPP contract. Although it is more usual, in particular in common law jurisdictions, to deal with a change of economic conditions through variation regimes, force majeure, MAGA and change in law provisions (as detailed in the previous section and below), some PPP contracts have included the underlying equitable principles of these legal principles explicitly or indirectly, by reference to the project economic and financial scenario updated in accordance with a project accounting plan and key economic indicators. These legal concepts are applicable to new, unexpected conditions of various kinds, and can significantly mitigate the risk to the private partner in case of major changes caused by technological disruption. They may, however, also be activated in favor of the contracting authority. Under these legal principles, the private partner facing an excessive loss that threatens to strand the asset may be allowed to request an adaptation of the contract to the new conditions to restore the economic balance of the contract, up to a certain threshold. Typical legal mechanisms that can be found in PPP contracts and legal doctrines that have already been invoked by contractual parties in the context of disruptive events in the past are summarized below.1 Restoration of the economic equilibrium In many jurisdictions, in particular in France and those influenced by the French Civil Code, notably in francophone Africa, the parties of a PPP contract have the right to adjust the contract to new, unexpected conditions and to “restore the economic balance” of the contract, irrespective of the existence of a contractual provision (right to financial equilibrium). Economic rebalancing refers to the practice of modifying the financial conditions that were agreed as part of the original contract. The intention is to preserve or restore the original economic equilibrium of the PPP contract. Rebalancing mechanisms are stipulated in many civil law jurisdictions (e.g., several countries in Latin America). In comparison to similar provisions in common law jurisdictions, they are more fluid mechanisms to deal with a variety of issues, including a force majeure event, a scope change, change in macro-economic conditions, change in law, or a major change to demand. The adjustments can be ad hoc responses to external events, such as a change in the rate of inflation, or be the result of contract renegotiation.2 For example, if the implementation of new tolling technology in a road project increases toll revenue in a PPP road project, the contracting authority could invoke the doctrine to achieve a sharing of excess profits or a reduction to the contract period, or to ask the private partner to lower the user tariff. The legal consequences range from a temporary relief from contractual obligations; an adjustment of the legal obligations to restore the economic balance up to a certain threshold (e.g., payments by either party); or compensation; up to a termination of the contract. Hardship doctrine Hardship doctrines are typically civil law principles that provide the private partner with relief where the contract circumstances have changed due to events that were unforeseeable, beyond the parties’ control, and that have a fundamental impact on the economic balance of the contract. French law, for example, allows a party to invoke the doctrine of hardship (imprévision) if there has been a change in circumstances unforeseeable at the time of conclusion of the contract that makes performance of the contract “excessively onerous” for one party that had not agreed to assume the risk.3 The affected party may request a renegotiation of the contract from the other party (e.g., to increase the contract price). Performance of the contract shall continue during the renegotiation. If the renegotiation is refused or if it fails, the parties can mutually agree to terminate the contract or ask the courts to adapt it. If an agreement cannot be reached within a reasonable time frame, the court can, upon request by one of the parties, revise the contract or terminate it, e.g., if the price increase is too significant or the situation is likely to last indefinitely.4 Parties may, however, derogate from this provision if they wish to do so. Market practice may exclude the doctrine of hardship in PPP contracts in order to provide certainty and instead rely on specific provisions in the contract. Box 8: Legitimate Expectations under the Energy Charter Treaty Following the financial crisis of 2008, the legitimate expectations doctrine under the Fair and Equitable Treatment clause in the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) was the basis of several claims by renewable energy developers against contracting authorities in Spain, Italy, and the Czech Republic. Spain and Italy, for example, had issued attractive incentives for investing in renewable energy before 2008, which were then rolled back in the years following the crisis. Many cases were brought under the ECT based on the legitimate expectations set by these incentives (set out in the legal and regulatory framework or through representations to the investor). Though tribunals have been split on this matter, many tribunals have sought to balance the competing interests between the investor and the state. In Charanne B.V. (Netherlands) Construction Investments S.A.R.L. (Luxembourg) v. The Kingdom of Spain, for example, the tribunal cited the good faith principle of customary international law a rule according to which host states cannot induce foreign investors to make investments based on “legitimate expectations” then later ignore the commitments that served as the basis for these legitimate expectations. It also established that legitimate expectations should be based on an objective standard, and that investors should exercise due diligence when investing (including meeting the standard of a “prudent investor”). Furthermore, it found that the expectations should be reasonable and proportional. Namely, the tribunal noted that no investor can expect from the host state that it will not change its regulatory framework in the public interest, and there was no promise from the state that the tariff regime would remain untouched for the entire life of the plant (had there been a stabilization clause in the treaty or in the investment agreement, it may have been read differently). At the same time, the investor has a legitimate expectation that, when modifying the existing regulation based on which the investment was made, the state will not act “unreasonably, disproportionately or contrary to the public interest.” Where the state did reduce the reasonable return of the investor, as was the case in PV Investors v. Spain, the tribunal found for the investors. Legitimate expectations and fair and equitable treatment The doctrine of legitimate expectations is generally recognized as a part of the Fair and Equitable Treatment clause found in many investment treaties. The concept of legitimate expectations arises “where a Contracting [Authority]’s conduct creates reasonable and justifiable expectations on the part of an investor (or investment) to act on reliance on said conduct, such that a failure by the [Contracting Authority] to honor those expectations could cause the investor (or the investment) to suffer damages.”5 The arbitral tribunals looking at these cases have found that the contracting authority can create these expectations in several ways: (i) through contractual rights, (ii) formal and informal representations to the investor (noting that certain tribunals further stipulate that these representations must be specific), and (iii) the general regulatory framework in force at the time of the investment. Importantly, the need for states to maintain a stable and predictable regulatory framework is not absolute, and is limited by the state’s sovereign right to regulate in the public interest. The specific context matters too when tribunals have looked at legitimate expectation claims: developing countries in transition, for example, cannot be expected to have legal regimes as stable as those of developed countries. Doctrine of frustration of purpose The principle of frustration refers to situations in which performance of a contract becomes worthless to a contracting party. Such a principle was sometimes invoked successfully in litigation related to COVID-19 and may also become relevant with regard to impacts caused by other disruptive events. The doctrine applies whenever circumstances that have become the basis of a contract have changed in a way that makes it unbearable for one party to perform its obligations under the terms of the contract. The changes must so significantly alter the nature of the outstanding contractual rights and/or obligations from what the parties could reasonably have contemplated at the time the contract was made, that it would be unjust, in the new circumstances, to hold them to the contract’s literal wording. The parties may only invoke the doctrine, however, in exceptional cases. It is not sufficient that the performance of contractual obligations becomes more expensive or more difficult for one party. The changes must also be neither within the control of the parties nor have been foreseeable by the parties at the time they entered into the contract. In these cases, the party affected may be permitted to stop performance or to request adjustment of the contractual terms to the new circumstances considering their contractual intent as far as possible. The range of possible contract amendments is wide and could, e.g., include an adjustment of pricing rules, delivery obligations or technical and operational rules. Amendments may also terminate the contract if the contract cannot be adjusted or if it would be unreasonable to do so. Additional consequences, e.g., compensation for any valuable benefit provided, differ depending on the jurisdiction and national legislation. Doctrine of impossibility The doctrine of impossibility may be used as a defense in situations where the actual performance of the contract has become impossible. Much like frustration of purpose, there are strict requirements that must be met to invoke this defense, namely the occurrence of a supervening event, the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which both parties made the contract, that makes performance under the contract impossible (or impractical). Mere unprofitability is not enough to render performance impossible.6 The doctrine has, for example, sometimes been invoked successfully by businesses in connection with impacts caused by COVID-19. If the doctrine is applicable for a specific PPP contract, it could help in a situation where the performance of contractual obligations, e.g., operation of a port, has been made impossible due to a mandated lockdown. Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: Whether or not legal doctrines that allow for a rebalancing of the economic equilibrium of the PPP contract are applicable and to what extent depends on the underlying governing law. For long-term PPP contracts, it can be advisable to spell out legal concepts that govern a PPP contract in a specific jurisdiction to achieve more clarity for both parties. Depending on the circumstances [and the specific jurisdiction], equitable principles could also be integrated into PPP contracts in jurisdictions where such principles are not mandated by law, to provide better protection for both parties in environments that are continuously changing due to technological progress, e.g., by referencing the project’s economic and financial scenario (which is updated from time to time) and key economic indicators. Several remedies exist in established contract law and PPP practice that are designed to deal with sudden shocks and emergency situations. If disruption in connection with new technologies prevents either party’s ability to perform their obligations under the PPP contract, both parties may be able to invoke force majeure provisions. Force majeure events are events beyond the control of the parties that render the performance of all, or a material part, of one party’s obligations impossible.7 The aim of force majeure provisions in a PPP contract is to allocate the financial and timing consequences of force majeure events between the parties. The starting assumption is that the risk of a force majeure event is a shared risk because it is outside both parties’ control.8 Each party will typically bear its own consequences of a force majeure event. Whether or not the parties can invoke force majeure provisions depends on the specific wording of each PPP contractual provision, the situation, and the definition of force majeure events. Usually, a force majeure clause will list out specific events that qualify, such as political events (war, strikes, protests) and natural disasters (floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, other “acts of God”). The definition often focuses on events that are uninsurable, outside of the control of either party, or catastrophic in nature. Force majeure clauses may specifically mention cyber attacks, but often they are not expressly included in the list of force majeure events. If the PPP contract contains an open-ended catch-all definition that includes all events beyond the reasonable control of the affected parties, the provision may cover scenarios where cyber incidents lead to widespread disruption that makes performance of the PPP contract impossible.9 Many of the adverse consequences described above that may increasingly affect PPP contracts as a result of rapidly changing technology,10 such as a drop in demand or obsolescence, are, however, very different in nature to the types of events that are listed in a standard force majeure provision and will therefore not qualify as a force majeure event. In order to invoke force majeure provisions, a force majeure event must further prevent a partner from fulfilling its obligations under the contract. The inability to perform obligations under the PPP contract may be caused directly by the disruptive event, e.g., a cyber attack prevents the operation of an airport for an extended period of time. Alternatively, the disruptive event may have indirect consequences, such as a fall in demand, rising costs, liquidity issues, or delays in the supply chain, which may make it impossible for a party to perform its obligations under the PPP contract. Force majeure provisions are, however, generally interpreted strictly and narrowly.11 It will usually not be sufficient for a party to claim, for example, that a cyber incident has made the performance of contractual obligations more expensive or more difficult. If force majeure is invoked, the contract may specify that the parties meet to draw up any mitigation measures and to negotiate any possible relief. The availability of insurance to cover the event and the duration of the force majeure event will affect what types of and how much relief is available. The most basic relief is an excuse from performance on the part of the party invoking force majeure. Relief may or may not also include compensation in terms of ongoing payments, extension of contract, a reduction in the performance requirements, or increase in tariff (corresponding to costs related to force majeure), depending on the circumstances and the risk allocation in the contract. Usually, the affected party will need to demonstrate ongoing mitigation efforts to qualify for any relief. As a contractual provision (rather than relief provided under statutory or common law), force majeure clauses can vary widely and the scope of events that qualify as force majeure and the relief available to a party impacted thereby will depend upon the specific language used in a contract. If force majeure is continuing for a specific amount of time, then either party may seek to terminate the contract. Force majeure provisions and their interpretation have recently received a lot of attention in relation to climate shocks and stresses. Historically, natural disasters have been considered force majeure events that are out of the control of all PPP parties. However, with the increased frequency of climate change-related disasters, it is more often acknowledged that infrastructure assets of the future need to be resilient to climate change, i.e., need to be planned, designed, built and operated in a way that anticipates, prepares for, and adapts to uncertain and potentially permanent effects of climate change. Against this background, it may not be justified to treat more foreseeable shocks and stresses that have become more likely due to climate change as force majeure going forward, while exceptional climate events may still qualify as force majeure events.12 This risk allocation will also incentivize adaptation measures and enhance resilience. Box 9: Japan—PPP Contracts Include Nuanced Force Majeure Definition Building on Experience from Previous Disasters The “Guidelines for Contract: Points to Consider for PPP Project Contracts” released by Japan’s PPP/Private Finance Initiative (PFI) Promotion Office include a standard force majeure definition. However, this standard definition is refined for each project or area, taking into account the characteristics and site conditions of each project. For example, Sendai City has iteratively clarified the contractual force majeure provisions based on lessons learned from various earthquakes and increasing project experience, and specified the seismic intensity as a numerical standard above which an earthquake is regarded as a force majeure event. In the Aichi Road Concession Project, the contracting authority defined, for instance, precisely the threshold that renders a natural disaster a force majeure event for which it bears additional costs if the concessionaire cannot foresee or cannot be reasonably expected to establish measures to prevent additional costs. Source: World Bank, Tokyo Disaster Risk Management Hub, and Global Infrastructure Facility. 2017. Resilient Infrastructure PPPs, Contract and Procurement: The Case of Japan, Solutions Brief. Likewise, epidemics and pandemics are treated in some PPP contracts as force majeure events,13 whereas the provision could not be invoked in other jurisdictions with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic.14 In the latter case the contracting parties could often rely on legal principles, such as the doctrine of impossibility or hardship clauses. Going forward more nuanced provisions that take potential precautionary measures into account may be necessary. Similar considerations apply if the increased use of disruptive technology together with a high level of connectivity makes the risk of cyber attacks that target infrastructure assets during the duration of a PPP contract more likely. They may not apply if the impact could have been prevented or mitigated by reasonable precautionary cyber security measures. Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: It will be important to assess and allocate potential risks created by disruptive technology and clearly define the atypical and extreme events that should fall within the ambit of the force majeure provisions together with thresholds and exceptions where appropriate and what the consequences are for each. To increase certainty and depending on the level of risk, contracting authorities should, for example, expressly mention cyber attacks as force majeure events. To ensure that cyber incidents that can be anticipated and prepared for do not qualify as force majeure events and to promote the adoption of cyber risk-reducing actions, PPP contracts should also describe under which circumstances cyber attacks should be treated as shared risk events, i.e., concrete precautionary and mitigating measures. A relative of force majeure, the material adverse government action (MAGA) provision is designed to provide relief to the project company where the government has taken or omitted an action that has a material adverse effect on the project company, such as its financial standing, through no fault of the project company. The provision allocates certain agreed types of political risk to the contracting authority, addresses the consequences of such risks occurring, including possible termination, and provides the private partner with appropriate compensation.15 MAGAs, also known as political force majeure events, are events - such as wars, riots, or expropriations or failures of governments to grant permits - that prevent the private partner from fulfilling its obligations under the contract. They often encompass change in law as well. Where the government takes action to prevent or respond to disruptive events, the parties may be able to invoke MAGA provisions. These could include an embargo or restrictions on movement, foreign exchange controls, or even nationalization (direct or indirect). Disruptions caused by cyber criminals, which have become a realistic threat for the provision of essential infrastructure services, may lead to a government action that qualifies as a MAGA event. In addition, unilateral changes of the support mechanism that alter the economics of the project can make a project that was initially very attractive for the private partner completely unattractive and give it the right to invoke MAGA or change in law provisions (for details on change in law provisions, see Section 4.2.3 (v)). For example, to attract investment in renewable energy projects, governments have in the past often offered a variety of support mechanisms, primarily as subsidies or attractive tariff arrangements. Renewable energy projects have been vulnerable to changes of these favorable conditions over the term of the contract. These policy changes can have different causes, such as plummeting renewable energy prices or changing macroeconomic circumstances. During the 2008 global financial crisis, for example, many European countries retroactively reduced the financial support afforded to investors in solar PV projects. When discussing whether an event is “material,” the following generally needs to be considered The extent to which a government action qualifies as a MAGA will depend on how the terms are defined under the contract, as well as the reasonableness of the actions and the outcomes of negotiations.16 Similar to force majeure provisions, MAGA provisions should clearly and specifically define the events and circumstances for invoking the clause and the rights and obligations of the private partner.17 Although project sponsors are expected to take commercial risks, drawing a line can be difficult; hence specific and narrow drafting of such clauses is advised, for example, using a defined list of covered events, not only to avoid disputes in their interpretation, but also to limit the extent of liability of the government under such clauses.18 Regardless of the definition, such events are distinct from force majeure in that they are considered within the government’s control and therefore the onus is usually on the government to “make whole” the private partner if it suffers any damages.19 Some MAGA events that cannot be controlled by either party are typically treated as shared risk similar to force majeure. Remedies may include relief from performance (including payment of delay liquidated damages where there may be delays), extension of time, and compensation for costs incurred as a result of the MAGA. However, where the government feels forced to take action as a response to circumstances that are not in its control, it is not clear whether this clause can be invoked instead of force majeure—though, it is possible the private partner will try, given that the remedies are usually better than under force majeure.20 Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: Similar to force majeure provisions, atypical and extreme events that fall within the scope of MAGA provisions and could become more frequent in relation to emerging technologies should be defined clearly—together with thresholds and exceptions so that the parties have suitable mechanisms within the PPP contractual framework that incentivize the implementation of precautionary measures, as well as appropriate response and mitigation plans that facilitate finding a balanced solution for both sides in case such an event occurs. Insurance plays a key part in managing force majeure and MAGA events, in particular climate change risks and risks posed by disasters and other unforeseeable events. Under some PPP contractual frameworks, the private partner is the main bearer of disaster risks and is mandated by the contract to purchase necessary insurance to transfer such risks to the insurance market. Though insurance plays a key part in managing climate change risks and risks posed by natural disasters, it has its limitations when it comes to the economic risks that may be the consequence of technology disruption, such as business interruption or decrease in demand caused by disruptive technology, which usually are not covered by insurance policies.21 Cyber insurance programs are still not common but have gained more traction in recent years. Mandatory cyber insurance could play a more important role going forward for PPP infrastructure projects to deal with exponentially increasing cyber risks caused by rapid digitization. Box 10: Mandatory Insurance for Natural Disasters for PPPs in Chile Chile sits on the Ring of Fire and has some of the most seismically volatile land in the world. The earthquake risk in Chile is therefore high during the course of a PPP. Because of their frequency, earthquakes are not considered as force majeure events under the PPP Law in Chile (Public Works Concession Law and Regulations - Ley y Reglamento de Concesiones de Obras Públicas). Instead, the PPP Law requires concessionaires to take out insurance that covers catastrophic risks that may occur during the term of the concession. The insurance payments obtained need to be allocated to the reconstruction of the asset, unless agreed otherwise. The concessionaire must repair the asset in its entirety and cannot claim reimbursement from the government. However, with regard to catastrophic events, the parties can contractually agree to share the losses. On February 27, 2010, Chile experienced an 8.8 magnitude earthquake, the second largest earthquake in its history. The earthquake caused significant land damage and triggered a tsunami that caused severe coastal damage. The United States Geological Survey estimated total economic loss as a result of the earthquake and tsunami at US$30 billion. The earthquake damaged and destroyed infrastructure, with losses estimated to be equivalent to US$21 billion. However, because most of the physical damage to ports, bridges, and roads built through PPPs was insured, the fiscal impact of the earthquake on the government in relation to these infrastructure projects was minimal. Sources: Ley y Reglamento de Concesiones de Obras Públicas, Articulo 36 et 75 (Public Works Concession Law and Regulations, Article 36 and 75); PPP Knowledge Lab. Climate Change and Natural Disaster. In a PPP project, the private partner will typically be expressly obliged under the PPP contract to comply with all applicable laws. An unexpected change in law may make the performance of its contractual obligations easier and less expensive—or may make it nearly impossible, delayed or more expensive. Changes in law provisions can, for example, become relevant when technological advancements require policy changes, if prices for technology are changing rapidly, or if new rules for an infrastructure developer or operators aimed at mitigating cyber risk are introduced. As a general rule, the private partner typically has to deal with the risk of a general change in law that affects any business and bear the costs of such changes. A legal requirement for all businesses to use electric cars would, for example, qualify as a general change of law. However, if the change in law applies to the PPP project only (discriminatory change of law) the contracting authority may have to grant relief from the breach or compensate the private partner for additional expenses. In these cases, if the change in law gives the private partner the right to terminate the contract, the contracting authority will have to pay termination payments that are similar to contracting authority default.22 Changes that only affect the specific sector in which the project company operates are known as specific changes in law. Mandatory technological enhancements are typically treated as specific changes in law. With regard to specific changes in law, there is a wide divergence of practices. A common approach is to share the risk—but to always provide a cap on the overall exposure of the private partner, so the risk is quantifiable. Considerations for Future PPP Contracts: Regulatory standards related to technology vary over time, and governments should not be prevented by long-term contracts with private partners from improving regulatory requirements to achieve higher efficiency, better safety standards, lower carbon footprints, or other public interests. However, it is considered best practice to limit or share the risk of the replacement or overhaul of technological equipment or systems, and any other cost related to regulatory technical enhancement—unless the requested technological upgrade is affecting the general economy and any type of business. If the new legal obligation was not possible to anticipate at the time of the contract execution, and this adversely impacts in a material form the financial equilibrium of the project, it is good practice to establish a financial relief mechanism in the contract to share and limit the cost impact. Change in law provisions should also define what qualifies as change in law, i.e., the types of “law,” qualifying date and what qualifies as a “change,” the approach to risk allocation, and the consequences in the event a change in law occurs. The term “law” is usually defined broadly (laws, regulations, government policies). See also Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, World Bank 2019, Chapter 3. How requests to change equipment to adapt to new technologies are dealt with depends on the specific circumstances and contractual provisions. For example, the private operator of a high-speed rail system may be obligated to implement new technologies if the enhancement has become best industry practice. In other cases, the contracting authority may be able to request a technological change under the variation provisions or, if the enhancement is prescribed by law or sectorial regulation, request the change as a legal requirement which could give the private partner the right to invoke change in law provisions. Sometimes, change in law is also captured under the material adverse government action provision (see Material Adverse Government Action (MAGA)). A PPP contract generally gives the private partner the right to claim compensation and time relief for certain defined events. Typically, these involve situations where the private partner has incurred unanticipated costs or delays, due to acts or omissions of the contracting authority or a third party, or due to force majeure events.23 PPP contracts typically distinguish between compensation and relief events: Compensation events are events for which the contracting authority broadly takes the risk because it is better placed than the private partner to bear or manage the risk. To the extent that the compensation event occurs during the term of the PPP contract, the private partner will be afforded sufficient protection in the PPP contract. The contractual protection varies and can, for example, be an extension of time, compensation, or any other form of contractual relief required to put the private partner back into the position it would have been in had the compensation event not occurred (“no better, no worse”). This principle applies to a number of contractual risks for which the contracting authority is responsible. Typical compensation events are discriminatory changes of law or authority failures. Relief events are generally external events that are outside the control of the private partner, which have a negative effect on the capacity of the private partner to perform its obligations under the PPP contract. They typically cause delays or increased costs beyond those anticipated in the financial model. They are also called delay events if they occur during the construction phase. Relief events are events for which the private partner is expected to take financial risk in terms of increased costs and reduced revenue but is given relief from other consequences of non-performance that such events cause, e.g., an extension of a deadline. These are, by nature, events that are either insurable or not expected to continue for many days. They typically include power or fuel shortages, accidental loss or damage to the project, and events such as fire, storms and floods, to the extent these are not covered by other contractual provisions. Temporary force majeure events, such as a cyber incident or non-discriminatory change in law caused by disruptive technology, may be treated as relief events.

Footnote 1: Trinity International LLP. 2020. Covid-19 – implications under French Law and guidelines for future project finance transactions; World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, S. 29. Footnote 2: GIH (Global Infrastructure Hub). PPP Contract Management. Footnote 3: Article 1195 of the French Civil Code. Footnote 4: Trinity International LLP. 2020. Covid-19 – implications under French Law and guidelines for future project finance transactions; World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, S. 29. Footnote 5: International Thunderbird Gaming Corporation v. The United Mexican States. Footnote 6: Dressel Malik Schmitt LLP. 2021. “Covid 19, Frustration of Purpose and Impossibility.” (Last visited September 13, 2022.) Footnote 7: At times the standard for relief is less than “impossibility”; for example, contracts may use lesser standards, such as“adversely affecting” or “preventing.” World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 8: World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, p. 27. Footnote 9: World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, p. 31 f.; World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 10: See Challenges of Disruptive Technology Footnote 11: Schwartz, A. 2020. “Contracts and COVID-19.” Stanford Law Review 73. Footnote 12: Global Center on Adaptation. 2021. Climate-Resilient Infrastructure Officer Handbook, p. 153. Footnote 13: On April 15, 2020, the Office of the General Counsel within the Ministry of Infrastructure in Brazil recognized COVID-19 as a force majeure event in order to allow claims related to the rebalancing of federal concession contracts (APP) in the sectors that fall within its jurisdiction, e.g., transport. However, the federal regulatory agencies in Brazil, e.g., the Electric Energy National Agency, discussed the rebalancing of concession agreements considering the COVID-19 pandemic. World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 14: According to the Guidance Note released by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) of the United Kingdom on April 2, 2020, in the context of Private Finance Initiative (PFI) and Private Finance 2 (PF2) projects, the government does not regard COVID-19 as an event of force majeure. Footnote 15: World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, p. 49. Footnote 16: World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 17: World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, Chapter 2. Footnote 18: World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 19: World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 20: World Bank Group. 2021. Covid-19 and PPPs Practice Note. Footnote 21: Measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic to limit the spread of the virus have, for example, significantly disrupted economic activity in countries around the world. This had major implications for infrastructure projects, including those financed through the PPP model, such as business interruption, decrease of demand, and supply chain issues. These pandemic-related losses were, however, typically not covered by insurance policies taken out by construction firms or infrastructure operators. Footnote 22: World Bank Group. 2019. Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions, p. 59 ff. Footnote 23: As described above, under force majeure, MAGA, and change in law, disruptive technology may lead under certain circumstances to compensation or relief events that need to be managed.PPP Contractual Provisions and Legal Mechanisms that Permit Adjustments in Exceptional Situations

Legal concepts underlying contractual adjustments

Force Majeure

Material adverse government action (MAGA)

Insurance

Change in law

Compensation and relief events

The Disruption and PPPs section is based on the Report "PPP Contracts in An Age of Disruption" and will be reviewed at regular intervals.

For feedback on the content of this section of the website or suggestions for links or materials that could be included, please contact the PPPLRC at ppp@worldbank.org.

Updated: May 3, 2024

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary for Disruption and PPPs

Disruptive Technology, Infrastructure and PPPs