Key Issues in Developing Project Financed Transactions

Photo Credit: Image by MichaelGaida from Pixabay

This section looks at some of the key issues that arise in project financed deals:

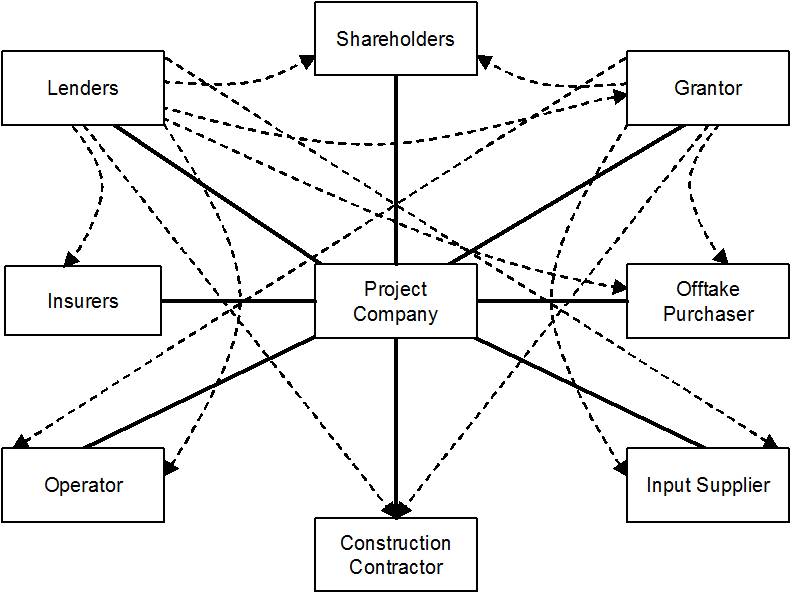

As noted above, the project is unlikely to generate revenue until the operations period and so it is going to be key to lenders and other investors that the revenue stream is certain and that forecasts of revenues are accurate. Future forecasts of demand, cost and regulation of the sector in any relevant site country will be important to private sector investors considering the revenue prospects of the project. For example, they may wish to: The project participants must ensure that the project has received all necessary approvals from the host government and any local authorities, and that the government will not change its regulation of the project's operation in such a way as to inhibit the project development and production plans, or the revenue stream. This risk is often difficult to manage in particular in countries with developing or highly volatile legal and regulatory structures. The project company will want to review the reasonableness of sanctions for failure to operate to the standards required, the payment structure for financial penalties, and any further sanctions for project company breach. The project structure should be reasonable and flexible, especially where the project in question is to continue over a long period, as the incentive mechanisms may need to change to ensure efficiency as the project evolves over time. Lenders will also seek to have trigger events, which allow lenders additional rights and powers in the event of their occurrence (for instance, if certain ratios such as debt to equity ratios or debt service cover rations are breached by the company). Given the priority of lenders to ensuring security of the project revenue stream, a number of financial ratios will be key to the analysis of a project financed transaction. Financial ratios can quantify different aspects of the project company’s business and operations and are an integral part of analyzing its financial position. During due diligence, before financial close, lenders will run these ratios using various sensitivities, for example testing the financial ratios in the event construction costs increase by 20%, or revenues fall by 10%. After financial close, the lenders will use these ratios as part of the project monitoring and control functions. Where ratios do not achieve the levels required, the lenders will have a series of possible interventions including blocking dividend distribution, sweeping cash from existing accounts, applying reserve account money to debt service, taking control of additional rights of the borrower or its shareholder. If these breaches persist, eventually, such breaches will amount to events of default permitting the lenders to accelerate, cancel outstanding loan amounts or suspended existing loans. It may also permit them to increase the interest margin, require compensation of the lenders for additional investigation costs and other fees and fines. The following are some of the main ratios of interest to lenders: A company’s debt to equity ratio is calculated as long-term debt / shareholders' equity. The lenders will prefer a lower debt‑to‑equity ratio in order to ensure a greater investment from the shareholders, ensure shareholder commitment to the project, increase the net value of project assets, and provide the lender with comfort that there is a good “equity buffer”[1]in the event that the project company gets into difficulties. Shareholders, on the other hand, will want a higher debt‑to‑equity ratio, decreasing the amount of investment they will need to supply and, since the return on debt contributions is fixed, increasing the potential return they can obtain from their equity contributions. The actual agreed debt‑to‑equity ratio will be the result of a compromise between the project company and the lenders, based on the overall risk to be borne by the lenders, the project risk generally, the nature of the project, the identity of the sponsors, the industrial sector and technology involved, the value of the project and the nature of the financial markets. For example, debt‑to‑equity ratios for power projects in developing countries tend to be in the order of 80:20 to 70:30, while other projects with higher market risks may not exceed 60‑65 per cent. debt. The LLCR is the net present value of available cash for debt service up to the maturity of the loan, divided by the principal outstanding. It is expressed as a ratio representing the number of times the cashflow (over the scheduled life of the loan) can repay the outstanding debt balance. To verify that the total outstanding debt is not at risk from a shortfall, lenders will apply a minimum LLCR to ensure that the total revenue available to the project company over the life of the loan is adequate to repay and service the total amount of debt outstanding. The amount of payment due to the lenders by the project company at any given time is called debt service, and making those payments is known as servicing debt. The lenders will want to be sure that as and when each payment obligation of the borrower arises, the borrower will have the money available to pay that amount. The lenders will therefore analyse, through the project financial model, the ratio of total amount of revenues available for debt service (e.g. net of operating costs, insurance premia, taxes, etc., but before equity distributions) during a period and compare this to the amount of debt service owed. The DSCR measures the amount of cash flow available to meet periodic interest and principal payments on debt. Unlike the LLCR, it examines the project company’s ability to meet its debt payments with reference to a particular period of time, for example annually or semi-annually, rather than over the life of the loan. This assessment can be made forward or backward looking. Rate of return (ROR) or return on investment (ROI), or sometimes just return, is the ratio of money gained or lost on an investment relative to the amount of money invested, usually on an annual basis. It includes return earned on both debt and equity. Internal rate of return (IRR) is the discount rate that results in a net present value (NPV) of zero of revenues over the project period, which shows the annualized effective compounded rate of return which can be earned on the invested capital (again, both debt and equity). Return on equity (ROE), on the other hand, strips out the return committed to debt servicing, providing equity investors with a picture of their return over the period of the project. Private sector shareholders will expect a high rate of return when they provide equity funding for a project. WACC is used to measure the project company’s cost of capital: the value of its equity plus the cost of its debt. WACC is calculated by multiplying the cost of each capital component, such as share capital, bonds and long term debt, by its proportional weight and then adding these components together. Assuming that interest charged on debt is much lower than the returns sought by equity investors, increasing the amount of debt also increases equity return. This is because the total amount paid by the project company in respect of its debt and equity (measured by its WACC) will be lower compared to a project fully equity financed, thereby leaving the project company with more funds for distribution and an increased ROE. It also allows investors to spread precious equity capital over a greater number of projects (as total equity investment required for each project decreases through better leverage), allowing investors (in particular those with specialist sector expertise – sponsors) to undertake more projects, and thereby deliver more infrastructure. In a project financed transaction the lenders will want to ensure that the revenue stream is protected and that the project performs as it is supposed to perform so that the lenders recover their loan and the project company does not default on its loan. Lenders will therefore require that there are a number practical control mechanisms of the company, such as limitations on what the project company can do without lender approval and the ability to step into management of the project company in the event the project is not performing, and that they take security over project assets. The project company will be required to covenant to the lenders that it will not (amongst other things) change the project plan, project contracts, capital expenditure program or debt program without lender consent. These are the key elements of the project, which the lenders will want to control to restrict changes in their underlying risk profile. The lenders will want the project company to provide warranties and representations concerning the financial, legal and commercial status of the project company, and the construction, operation and performance of the works. The lenders will also want the project company to provide a series of undertakings in relation to the project documents and the project company's compliance with its obligations. These will include "reserve discretions" whereby the project company undertakes not to act on certain of its rights and discretions under the project documents without lender approval or to act on rights and discretions at the instruction of the lenders. Representations and warranties are often divided between positive and negative undertakings. Typical borrower undertakings include: Positive undertakings: Negative undertakings: The warranties and representations will be used by the lenders not so much as a basis for claiming damages but rather as potential events of default which permit the lenders to suspend drawdown, terminate, demand repayment and enforce security. The lenders will want the project company to repeat certain warranties and representations with each drawdown and periodically throughout the life of the loan, to ensure continued compliance. In the case of termination of the concession agreement, the lenders will have security over the project assets. However, the project assets are likely not to be worth the value of the outstanding debt. Therefore, the lenders often require some form of right to take over the project where the project company has failed in its obligations and the grantor intends to terminate the concession agreement or the offtake purchase agreement. Step‑in provisions give the lenders the right to step in to the project company's rights and obligations under the project documents. The lenders will want to ensure that the grantor is in a position to continue with the project after step‑in. However, the lenders themselves will not want to be involved in the actual step‑in. They will generally mandate a "substitute entity" to step in for them. The step‑in regime is usually included in direct agreements between the lenders, the grantor and the project participants. It can involve three different levels of lender intervention in the project: cure rights, step‑in rights and novation or substitution. As noted above, step‑in rights like security rights in project financing are generally considered to play a defensive, rather than an offensive, role. Cure rights allow the lenders to cure a breach of an obligation by the project company under one of the project documents, including in particular the concession agreement. Each of the project participants will be required to inform the lenders of a relevant breach and allow the lenders to cure that breach. Where the lenders do not exercise their right to cure within an established cure period, the relevant project participant may proceed under its contractual remedies. Lenders will generally be hesitant to involve themselves in the cure of a project company breach unless the cure is limited to the payment of amounts due. The lenders may want the opportunity to cure before having to decide whether to step in, for example the default may simply require the payment of monies, but otherwise the project company is performing well. Step‑in rights arise where the project company breaches one of the project documents and the relevant project participant chooses to terminate. The lenders are given a chance to step in with the project company, cure the relevant breach and put the project back on track. The other project participants will be required to continue their contractual relationships with the substitute entity in lieu of the project company, although the project company will not be released from its obligations under the project documents. The lenders will also be permitted to step out where they choose to do so, without incurring any continuing liabilities. The project company would remain liable both during step‑in and after step‑out. Step‑in rights will also be available for each of the project documents. A third level of step‑in involves novation of all of the project company's rights and obligations to a substitute entity, in which case the substitute entity, for the purposes of the project, takes over the project company's role and the project company is removed from the project. The concession agreement, each of the other project documents and any licences or permits will need to provide for novation or be renegotiated before the lenders can successfully novate the project to the substitute entity. The various project participants may require the right to approve the substitute entity, although they should not be permitted to delay or withhold such approval unreasonably. The lenders and the grantor may enter into direct agreements with the project participants to cover issues such as security over project assets, secondment of personnel, accommodation and costs. Similarly, these direct agreements may consider the management of know‑how between the project participants and the project company including transfer, duration, licensing rights, exclusivity, distributorship, and the supply of spare parts, goods or raw materials. Direct agreements may contain collateral warranties in favour of the lenders and the grantor and will set out step‑in rights, notice requirements, cure periods and other issues intended to maintain the continuity of the project where the project company defaults and/or falls away.[2] Illustrated below are some of the many direct agreements that may exist in a BOT project. For example, the direct agreement between the construction contractor and the grantor, giving the grantor access to warranties of the construction works in the event of project termination. The lenders to a project financed project will want to put in place as much security for the financing as possible. Security is both "offensive" and "defensive": offensive to the extent the lenders can enforce the security to dispose of assets and repay debt where the project fails; defensive to the extent that senior security can protect the lenders from actions by unsecured or junior creditors (ie creditors that rank below them in priority of being repaid and in bankruptcy). In order for the lenders to have complete control, they will need to take comprehensive fixed and floating charges (which terms differ by country) over all project assets, which in common law jurisdictions may allow the lenders to appoint a receiver to manage the business in the event of insolvency. If such comprehensive security rights are not available, the lenders may seek to use ring-fencing covenants in an effort to restrict other liabilities, security over SPV shares to enable lenders to take control of the SPV or the creation of a special golden share that provides the lenders with control in the event of default. Security rights may also allow the lenders to take over the project rather than just sell the project assets, since the value of the project lies in its operation and not in completed assets.[3] The key mechanisms principal lenders to a project seek to secure their lending include: The nature of the security taken over project assets will depend on the provisions of the applicable law and negotiations between the lenders and the project company. In many countries, the law will prohibit the transfer of ownership of real property assets used for public services to the private sector or the government will retain reversion rights in those assets needed to provide public services, in order to ensure that no suspension or degradation of public services would result from termination or expiry of the project. In such cases the taking and/ or enforcing security over real property assets will be difficult or impossible. On termination, the project assets are generally transferred to the grantor, or to some other private party who will continue to provide services to the grantor. For this reason, on termination, the grantor is required to pay an amount of money that compensates the project company for the construction of that asset. The amount of compensation is usually a matter of extensive negotiation between grantor and the project company (and of great concern to lenders). In the event of termination for project company default, termination regimes vary, but focus primarily on some portion of the market value of the underlying asset, or if this is not feasible, the reimbursement of the outstanding amount of senior debt at the date of termination, based on lending arrangements that have been approved by the grantor. The intention is to pay for the asset transferred to the grantor on termination. By sizing compensation to the amount of senior debt (and not any equity or other costs), the shareholders are motivated to support the project company, and the lenders are encouraged to lend to the project. Senior debt may not be paid out completely in order to incentivize the lenders to use their best efforts to avoid project company default, thus, the grantor may want to compensate only a portion of senior debt. In more risky jurisdictions this may amount to 90-95%, while in more secure jurisdictions this may amount to 70-75% of senior debt. In the event of termination for grantor default, the project company will generally be compensated for debt, lost profit and breakage costs. The grantor will want to consider carefully the definition of these different elements of compensation to avoid the project company earning extra profit or being reimbursed for unreasonable or unnecessary payments made to third and associated parties. Termination that arises from "no fault" termination, e.g. extended force majeure, usually results in compensation for debt and equity capital but usually not lost profits and only some breakage costs. If the underlying assets are not transferred to the grantor, the nature of the underlying loss of the project company will be significantly different. Clearly compensation regimes are subject to market forces and will be heavily negotiated, and therefore the above should be considered an indication only of the termination regime that will apply in any given project. Also, any termination compensation regime must fit within the applicable legal regime and any restrictions that may apply to penalties or excessive interest. [1] Shareholders would be paid out after lenders in the case of an insolvency of the company and so equity is seen as a layer of protection, resource that the company can resort to using when in difficulty. [2] See chapter 29 of Scriven, Pritchard and Delmon (eds), A Contractual Guide to Major Construction Projects (1999). [3] This will be subject to local law.Certainty of Revenue Stream

Financial Ratios and Financial Covenants

Debt-Equity (D/E) Ratio

Loan Life Cover Ratio (LLCR)

Debt Service Cover Ratio (DSCR)

Rate of Return (ROR)

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

Lender Protection, Step-In, Direct Agreement and Taking Security

Warranties, Undertakings and Representations

Step-in

Cure rights

Step‑in rights

Novation

Direct Agreements

Taking Security

Termination compensation

Updated: July 22, 2024

Related Content

Financing and Risk Mitigation

Main Financing Mechanisms for Infrastructure Projects

Investors in Infrastructure in Developing Countries

Sources of Financing and Intercreditor Agreement

Project Finance – Key Concepts

Risk Allocation Bankability and Mitigation in Project Financed Transactions

Risk Mitigation Mechanisms (including guarantees and political risk insurance)

Government Support in Financing PPPs

Government Risk Management

Further Readings on Financing and Risk Mitigation