Ownership Models in Asset Recycling

Photo Credit: Image by Pixabay

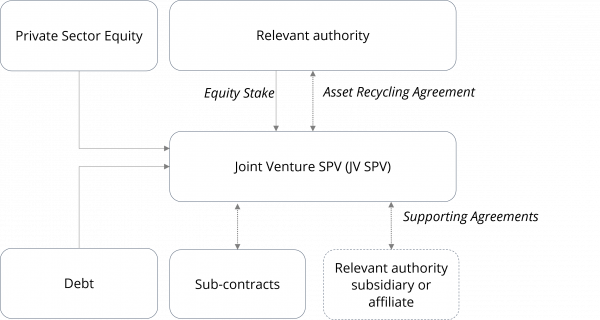

There are several variations as to how an asset recycling transaction undertaken by way of a concession or lease arrangement can be implemented. In this section, we discuss the following models: Concession / Lease Model – where the selected private sector investor(s) form a SPV to enter into an asset recycling transaction with the Relevant Authority by entering into a long-term lease or concession agreement to operate the asset. Joint Venture (JVC) Model – where the Relevant Authority and the selected private sector investor(s) enters into a Joint Venture to jointly operate the asset under a long-term lease or concession. Partial divestment – where there is a partial divestment in the shares of an asset holding company by the Relevant Authority. For the avoidance of doubt, these guidelines are specifically focused on concession/ lease model. Under this model, the asset recycling transaction is implemented through a newly established limited liability company formed by the selected private sector investor(s) as a special purpose vehicle (Private Sector SPV). The Private Sector SPV will enter into the governing agreement with the Relevant Authority relating to the long-term operations of the asset. One or more of the Relevant Authority’s subsidiaries or affiliates may also be included in the contracting structure under the following circumstances: The subsidiary or affiliate owns or holds rights to all or part of the project site and enters a lease with the Private Sector SPV and/or provides the Private Sector SPV with right of way or access to the project site. The subsidiary or affiliate provides the Private Sector SPV access to shared infrastructure; or The subsidiary or affiliate provides or sells goods (such as fuel or feedstock) or services to the Private Sector SPV and/or will purchase or acquire goods or services from the Private Sector SPV over the contractual term; or The subsidiary or affiliate has other rights and/or obligations relating to the relevant asset. Agreements with the subsidiary or affiliate should be considered supporting agreements. Under these circumstances, the subsidiary or affiliate should not be viewed as a substitute for the Relevant Authority. The Relevant Authority should be a party to the primary agreement with the SPV and should undertake that each relevant subsidiary or affiliate will comply with its contractual obligations to the Private Sector SPV, in a manner consistent with the agreed risk allocation. Figure 5: Structure of Concession / Lease Model As further explained under Risk Identification and Allocation, some licences, permits and approvals may be the responsibility of the Private Sector SPV, whilst others may be procured with the assistance of the Relevant Authority. We note that under this model, the Relevant Authority may also take a stake in the Private Sector SPV. For the purposes of this discussion, this variation is not discussed under the Concession Model to distinguish between the Concession and the Joint Venture Models. The former model is a wholly private sector concession/lease whereas the Joint Venture Model involves the Relevant Authority holding a stake in the on-going operations of the asset. A variation on the above concession/ lease structure is the joint venture (JV) model, where the Relevant Authority holds an equity interest in the Joint Venture SPV as a shareholder together with the selected private sector investor(s) (JV SPV). Figure 6: Structure of Joint Venture Model The Relevant Authority may hold shares in the JV SPV directly. It may also consider having their subsidiary (typically 100% owned, with appropriate guarantees from the parent, assuming that the subsidiary is not independently creditworthy) enter into the JV with the private sector partner and hold the shares in the JV SPV. This relationship will be governed by a shareholder’s agreement entered into between the Relevant Authority and a separate JV SPV established to represent the private sector equity holders collectively. Under this structure, the private sector equity holders vote together and provide the Relevant Authority with a sole point of contact. Meanwhile, the project agreement for the asset will be entered into between the JV SPV and the Relevant Authority. The JV approach may impact the financial attractiveness of the transaction to the private sector, including the following: The valuation of the Relevant Authority’s interest in the underlying asset that is subject to the asset recycling transaction. The proportion of the Relevant Authority’s economic interest as an equity holder in the JV SPV and its attendant voting rights. How any financing requirements will be addressed and the extent (if any) that the Relevant Authority can assist with or support any third-party financing efforts. Whether any private sector shareholder loans, subordinated debt or other financing sources will be permitted. Other issues which should be considered for a JV structure include the following: The proportion of the Relevant Authority’s voting rights as an equity holder in the JV SPV, and how that impacts the contractual rights of the Relevant Authority (or its subsidiary or affiliate) under other project documents. Share classes and related preferences and rights. Board representation and board level governance. Decision making procedures (including any protective provisions or consent rights granted to either the Relevant Authority or the private sector equity holder) and the procedure for resolving any 'deadlocks'. Under the concession / lease structure, the issues identified above are resolved amongst the private sector equity holders, and the Relevant Authority would have no exposure to these issues. In contrast, under the JV structure the issues identified above exposes and involve the Relevant Authority directly, and therefore must be considered together in relation to the overall risk allocation and attractiveness of the transaction. The typical concession / lease structure is usually considered to be simpler and more attractive to the private sector than a JV. However, there are some circumstances where a JV could be more appropriate for a particular transaction. These circumstances include: The asset has special characteristics, such as technical interface with other assets of the Relevant Authority (such as switchyards, transmission lines, pipelines, land and buildings, raw water supply, waste disposal facilities, stockpiles, fuel supply, terminals, private roads, etc.), that require close day-to-day coordination with the Relevant Authority to make the project successful. The business activity, including ownership constraints (if any), The transaction’s financial attractiveness is such that a minority portion can be retained by the Relevant Authority without deterring attractive bids from the private sector. Box 5: Special Considerations for JV Structure When using a JV structure, the Relevant Authority should consider the prospect of the project's overall success and balance its position accordingly. In many instances, the initial financial model will presume 100% private control to analyse whether the project structure will provide an appropriately attractive financial return. Introducing the Relevant Authority into the structure has the potential (1) to reduce the private sector's share of the potential return, and (2) to introduce additional related party payments (increased costs and expenses), thus making the project less attractive to private bidders when offered to market. The impact can be particularly acute under an equity carry model, where the private party finances all or part of the capital investment required including the portion of the Relevant Authority’s (e.g., if the project requires the private partner to redevelop the asset). Another important consideration relates to the control over the JV SPV between the Relevant Authority and the private party, which may create complications in the decision-making process and affect the ability of the private party to control and improve operations of the asset and, ultimately, to maximise the project’s financial return.Concession / Lease Model

Joint Venture Model

The Guidelines have not been prepared with any specific transaction in mind and are meant to serve only as general guidance. It is therefore critical that the Guidelines be reviewed and adapted for specific transactions To find more, visit the Guidelines to Implementing Asset Recycling Transactions Section Overview and Content Outline, or Download the Full Report.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. GUIDELINES FOR IMPLEMENTING ASSET RECYCLING

3. Guidelines for Asset Identification

Related Content

Additional Resources

Leases and Affermage Contracts

Type of ResourceJoint Ventures / Government Shareholding in Project Company

Type of ResourcePPP Reference Guide