The PPP Decree: an important re-boot for Vietnam’s PPP program

Photo Credit: Image by Katherine Slade from Pixabay

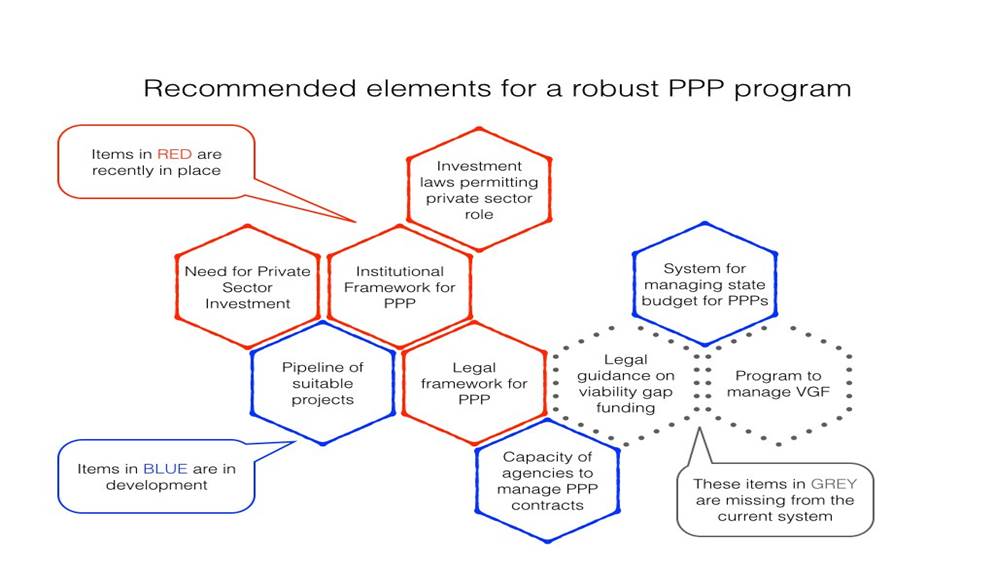

Authored by: Stanley Boots, Lawyer and CEO, Frontier Law & Advisory This article has also been cross-published on the World Bank PPP Blog. Click here to view. After over two years of development and drafting, Vietnam’s Decree 15 on Public Private Partnerships (PPP Decree) came into effect on 10 April 2015. Dedicated specifically to the identification, preparation and implementation of PPP projects, the PPP Decree replaced the largely unimplemented regulations for pilot PPP projects (formerly, Decision 71) as well as the regime for build-operate-transfer (BOT), build-transfer-operate (BTO) and build-transfer (BT) projects under Decree 108. The PPP Decree is an important re-boot for PPP in Vietnam. The earlier Decision 71 offered an ambitious vision but lacked sufficient detail to allow PPPs to be implemented. In addition it was deemed incompatible with the higher-ranking Decree 108 (on BOT projects) on some key issues such as differing caps on the permissible level of government support. Thus, PPP got off to a bit of a false start with Decision 71. In developing the PPP Decree, a number of lessons were taken from challenges faced by investors and Government alike under the previous regulations. The PPP Decree aims to offer a more consistent and effective regime for all PPP projects (including BOT, BTO and BT) and was drafted to provide more guidance for both State authorities and investors in order to facilitate project preparation and implementation. The PPP Decree was developed with a focus on improving the transparency of the project development process in order to promote more foreign investment in infrastructure development across key sectors such as transportation, energy, environment, water supply, waste treatment, etc. The PPP Decree introduces some new features that distinguish it from preceding regulations, including: A translation and overview of the features of the PPP Decree, as well as various analyses of the decree, may be found at this link. The PPP Decree addresses many of the former gaps in the legal framework for PPPs. Having learned from past difficulties in implementing new legislation, Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) has launched several initiatives to support the implementation of the PPP Decree. These initiatives are designed to give the overall environment for PPPs a stronger foundation, including: These initiatives are further discussed below. PPP Foundations Course: In parallel with the drafting of the PPP Decree, the MPI’s consulting team helped develop and roll out a PPP Foundations Course training central and provincial authorities on the core concepts of the PPP Decree and project level issues to be faced in identifying, preparing and tendering PPP projects. The purpose of the PPP Foundation Course is to ensure that the implementing agencies (referred to as “authorized state authorities” or “ASAs” in Vietnam) share a common understanding of the PPP Decree and how it is intended to work. MPI quickly assumed responsibility for the course, and to date has trained over 600 public sector representatives. Circular Drafting: MPI and the Ministry of Finance are cooperating on drafting various circulars for implementing the PPP Decree, including a circular on the tender process that includes criteria and templates for pre-qualification and bidding. It is hoped that these efforts will lead to circulars being in place when investors are invited to bid on the first pathfinder projects. Project Development Facility: The $30 million project development facility (PDF) addresses the persistent issue faced by ASAs in finding sufficient budget to hire quality transaction advisors to support the preparation, development, tendering and negotiation of PPP projects. The author’s experience has been that ASAs budget as little as $300,000 for the team of transactional advisors to a PPP project when funding comes form the ASA’s own annual budget. This is insufficient for PPP projects which are complex and require support from pre-feasibility study phase (called “project proposal” in Vietnam) through contract negotiation. Further, many ASAs are unfamiliar with managing their advisors or efficiently developing and negotiating project documentation causing inconsistency and delays (under the former BOT regime projects typically took over 5 years to negotiate, with additional delays in reaching financial close). The PDF seeks to address some of the practical project implementation issues by making available to ASAs sufficient budget to retain transaction advisors early in the project development. PDF support is now available and several projects have already been assessed through the project proposal stage in anticipation of soon tendering pathfinder projects. Standardized Project Documentation: Both MPI and the Ministry of Transport are developing standardized project document templates for use in PPPs. Standardized contract templates will help ASAs achieve greater consistency between projects and even across sectors. As noted above project development has been slowed by a lack of consistency during the contract phase. In past projects, ASAs have often requested investors to develop the draft project contract, as the ASA may not have sufficient capacity or advisory support to draft its own contracts. As a consequence, the ASA would be in a position of having to relearn the project contract for each deal, where (even using past precedents) the investor would draft new contract terms that are not familiar to the ASAs negotiators. Standardized documentation will allow ASAs to become fully familiar with “their own” documentation and better understand the effects of amending such familiar documentation. VGF Management: The next important step for Vietnam’s PPP program will be the development of a financial management system for State support of projects, including both VGF support and government guarantees. At this time, an in depth study of the Government’s options for a VGF (and possibly guarantee) management system is being undertaken by the authors who expect to present their findings to Government in the first quarter of 2016. The follow graphic illustrates how the above elements for a robust PPP program are now coming together in Vietnam. With the above elements finally coming together for the first time in Vietnam, it is hoped that Vietnam’s PPP program can finally have the re-boot needed to attract investment in the $16+ billion a year needed through 2020 to keep the economy on track. A number of development partners are now active in Vietnam’s PPP space. While these efforts are needed, the authors would urge for strong coordination between development partners to prevent duplication of work or inconsistent results. For more information, please contact Stanley Boots of Frontier Law & Advisory. Stanley Boots, lawyer and CEO of Frontier Law & Advisory, has 16 years infrastructure and PPP experience from Asia to Iceland. Today he leads a team of bold, relevant and disruptive" lawyers and advisors developing unique solutions to Southeast Asia's developmental needs (www.bold-frontier.com), especially in PPPs and private sector development.

Updated: November 26, 2020