Project Identification, Screening and Appraisal

Photo Credit: Image by Pixabay

On this page: Both governments and investors must consider longer-term planning in the project identification, screening and appraisal process, to ensure the sustainability of projects built today that will still be relevant in a world many years in the future.

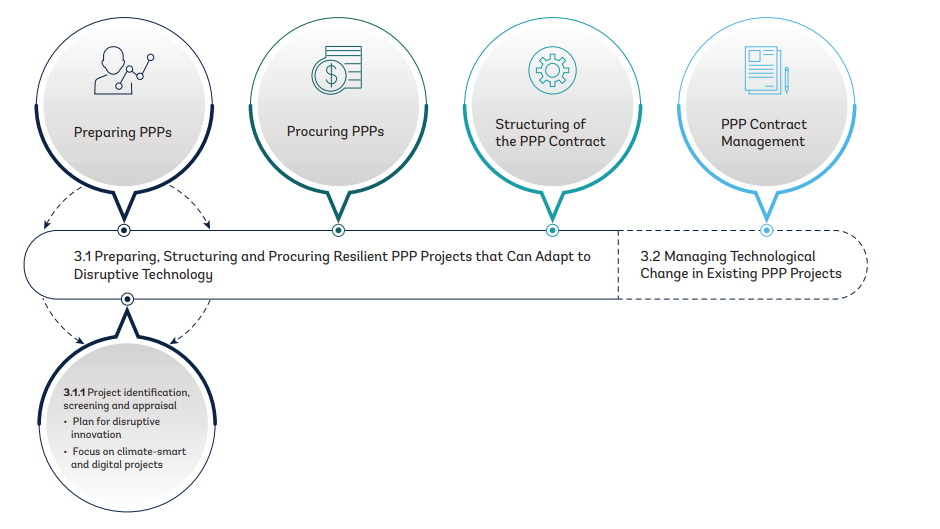

Both governments and investors must consider longer-term planning in the project identification, screening and appraisal process, to ensure the sustainability of projects built today that will still be relevant in a world many years in the future. During the project identification stage, governments identify potential projects and screen the priority projects in order to determine whether they have the potential to generate value for money (VfM) if they are implemented as PPPsGiven that PPP contracts are usually for a period of 15 to 35 years, it is important for both the government and the developer during this stage to look forward and consider if trends in technological development may impact their projects decades hence. For example, many governments increasingly want to prioritize digital and “green” infrastructure projects in these times of technological transformation and ambitious worldwide goals to cut carbon emissions. Thus, long-term investments in carbon-intensive sectors may become less attractive for governments and investors. Similarly, when planning urban projects, governments and investors may wish to consider trends towards smart and livable cities, with younger generations embracing denser urban centers with green spaces, cycling lanes, and public transport. Box 3: Importance of Assessments that Account for Technological Changes: European Stranded Assets in the Utility Sector, 2010–2015 The development of the European utility industry since 2010 offers valuable lessons about how quickly and dramatically seemingly stable industries can change, and what implications this can have for investors. In 2005 the utility sector in Europe was highly profitable. In most integrated power utilities, the generation business represented a majority of earnings, the power plants were seen as the core assets of the company, and mergers and acquisitions resulted in large players that forecasted a steadily growing demand—based on the assumption that 1 percent gross domestic product (GDP) growth would result in an increased electricity demand of 0.5 percent to 0.8 percent. The reality looked different. For the large utility players in Europe, a combination of falling energy prices, a push for renewable energy, advances in renewable power technology, energy efficiency improvements, and an economy that was weakened by the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 created a toxic mix of negative growth, low utilization of large-scale power plants, and substantial margin pressure. Total impairment for the 10 largest power utilities was €129 billion from 2010 through 2015, and accelerated at a rate of 24 percent per annum. Of these 10 power utilities, six have seen a share price drop of more than 55 percent, from 2010 to 2016. If this development had been predicted at least partly just a few years earlier, construction of new fossil plants would have been stopped earlier, and enormous value would have been saved. It is sometimes argued that this was not a black swan event, and that a large part of what happened was actually predictable. Although the financial crisis and the decrease in coal and CO2 prices was difficult to foresee, the policy makers’ push towards decarbonization and renewable power was largely predictable, and the changing electricity/GDP growth ratio should also have been foreseeable. Source: SEI (Stockholm Environmental Institute) and Material Economics. 2018. Framing Stranded Asset Risks in an Age of Disruption. Regulatory Asset-Based Approach (RAB) - Does a RAB provide a better protection against asset stranding in comparison to the PPP model? As mentioned above, one concern related to long-term PPP arrangements is that they may not be flexible enough to deal with unforeseen technological changes, in particular if they trigger structural changes in the market and asset stranding. Another model for private sector financing of infrastructure that has emerged and is sometimes discussed in this context is the Regulatory Asset-Based Approach (RAB). For many years, many regulated companies, such as utilities, have used this approach. Under the generic RAB approach, the regulated company owns, invests in, and operates the infrastructure asset. It receives revenue from users and/or subsidies to fund its operations and recoup the investment costs. An economic regulator sets the tariffs to be charged by the regulated company to end users of the infrastructure. In order to identify an appropriate tariff, the economic regulator monitors both the company’s operating costs and the capital investments which it makes in respect of the infrastructure asset. The regulator then includes, in the tariff, an amount to cover the allowed operating and maintenance costs, plus financing cost of the capital investments (the cost of equity and debt, including an allowed return). Tariffs are reviewed and adjusted periodically by the regulator. Regulators have developed different models and introduced performance-based frameworks that encourage innovation between reviews (see also Box 7: United Kingdom: Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem)—Framework for Price Control Incentivizes Innovation). In the context of disruptive technology the RAB model has in particular advantages regarding the renegotiation of tariffs versus the PPP mode. The RAB model in the framework of price cap regulation represents a regulatory contract in the form of a license -- with a string of renegotiations, I.e. price reviews. These allow adjustments to the changing environment without weakening the ex-ante commitment of the bidders or influencing the future expectations of investors. Renegotiations of a PPP contract are invariably less structured than in a RAB model, primarily, because there is no economic regulator in the background. However, while the RAB approach has been successful with regard to utilities it has also drawbacks that are explained in more detail in the sources listed below. One of the disadvantages is that the asset base of a regulated utility contains a collection of assets, with the result being that the individual assets are not subject to the same cost discipline as would apply to a PPP project. In addition, the effectiveness of the RAB depends on the quality of the regulator who needs to have the capacity and experience to control and monitor a number of infrastructure assets in order to set the right tariff, which may sometimes lack in developing countries. Sources: The Regulatory Asset Base Model and the Project Finance Model: A comparative analysis, International Transport Forum 2015. Resetting price controls for privatized utilities : a manual for regulators. Economic Development Institute of the World Bank, 1999 . Once the government has identified priority projects, the potential project will be appraised as part of a detailed business plan. After the high-level assessment during the screening phase, the project will undergo an in-depth analysis of its feasibility, risks, and potential mitigation measures, including the project’s value for money and its fiscal implications during the appraisal stage. Unlike disruptive events, which can be enumerated (such as in force majeure clauses), predicting future technology development and how it will shape infrastructure is almost impossible. However, governments should, for example, carefully identify the types of risks that need to be considered as part of project design and those that could jeopardize implementation and assess the potential use of InfraTech in the project's feasibility study. Indeed, future disruptive technologies are not necessarily black swan events. Though the exact impact of disruptive technologies may be difficult to predict, certain flexibility can be factored in when PPPs are prepared, with an understanding that disruptions and innovations in technologies, business, and policy can change the expected outcome of a project. Therefore, risks that are associated with potential technological changes need to be identified and assessed at this stage, including strategies that could mitigate these risks, whereas remaining risks need to be allocated carefully to the respective parties. At the same time, rapid35 technological changes make it necessary to assess how new technologies can be integrated into projects throughout all stages, and to find mechanisms to incentivize and facilitate innovation. The additional risk of obsolescence means that governments and investors need the capacity and expertise to determine technology trends in specific sectors, and to assess whether essential technology will likely change during the term of the PPP contract, making the infrastructure asset obsolete. In particular, technical developments that may lead to stranded assets need to be factored into the respective methodologies and risk assessments, including financial models. This is especially relevant for projects that are most affected by an accelerated shift towards low carbon technology. In addition, increasing digitization and use of disruptive technology in PPP infrastructure projects could make it necessary to use mechanisms similar to environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) going forward, to identify and assess potential adverse effects of disruptive technology on communities and the larger society as well as potential benefits. This includes the assessment of risks related to extensive data collection and surveillance as well as data privacy issues. If the use of disruptive technology includes the collection of private data, governments should ensure that they understand what entities collect, use, and own the data, and how the data can be protected after the project has been terminated. This topic cannot be covered extensively within the scope of this report. Guidance is needed in this regard, in particular if disruptive technology is implemented through PPPs in countries where regulation may be missing or where regulatory frameworks have gaps. Against this background, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) has recently developed a code of conduct relating to the management of risks arising from the adoption of disruptive technologies.1

Footnote 1: Myers, Gordon, and Kiril Nejkov. 2020. Developing Artificial Intelligence Sustainably: Toward a Practical Code of Conduct for Disruptive Technologies; IFC (International Finance Corporation). 2020. IFC Technology Code of Conduct - Progression Matrix. Public Draft.

The Disruption and PPPs section is based on the Report "PPP Contracts in An Age of Disruption" and will be reviewed at regular intervals.

For feedback on the content of this section of the website or suggestions for links or materials that could be included, please contact the PPPLRC at ppp@worldbank.org.

Updated: April 25, 2024

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary for Disruption and PPPs

Disruptive Technology, Infrastructure and PPPs